Hito Steyerl Interview

Your work is very complex, combining an art practice with theoretical writing. And you’ve produced a lot. In my mind, it exists as an entity – a very dense one. You could even say it has exceptional spatial characteristics. There is a particular conceptual reason for this: the web. When deciding how to approach a discussion with you, I realized the answer is obvious. We are doing this interview on the occasion of a number of exhibitions you are having in the UK and Germany; however, our immediate context is the site where this interview appears. So let’s talk about that – or at least focus our discussion in a way that will allow us to incorporate links, images and videos on this website.

One of the forms of your practice is the representation of data; or more specifically, its characteristic of being in motion, and so to a certain extent being beyond representation. I love that you take this on; it is so very defining of our contemporary existence and yet rather an elusive idea to conceptualize. It occurs to me that your work also represents this idea as it is manifest in the contemporary condition of the dispersal of attention, which is something I know I struggle with. As if to prove my point, while writing this question, I checked my Twitter feed and clicked on this link, a rather tongue in cheek screed about the Evils of Saving. http://www.observer.com/2010/daily-transom/evils-saving. So with this web-induced diversion of my attention, I find an analogy for the subject at hand: Capital too wants to be in motion. So that’s my question. In so far as your work engages with form in its most contemporary manifestation, is that your true subject: Capital?

HS: Lets step back a little and consider the relation of Capital and movement. Whilst Capital, for sure, is moving, this doesn’t necessarily mean that every movement is fully captured by Capital. There is an asymmetrical relation between both. Movement – as for example in the case of diverted attention online – can also constitute a flight from labour or other capital-based relations (of course these evasions are immediately recaptured, but again not fully). Capital is not able to fully come to terms with evasion, resistance, distraction, irritation, sleepiness.

I am fascinated, though, with the ways Capital registers digitally, how it becomes visible, how it matters, so to speak. One might like to think that it is purely abstract and invisible, but it leaves stains and traces as it moves.

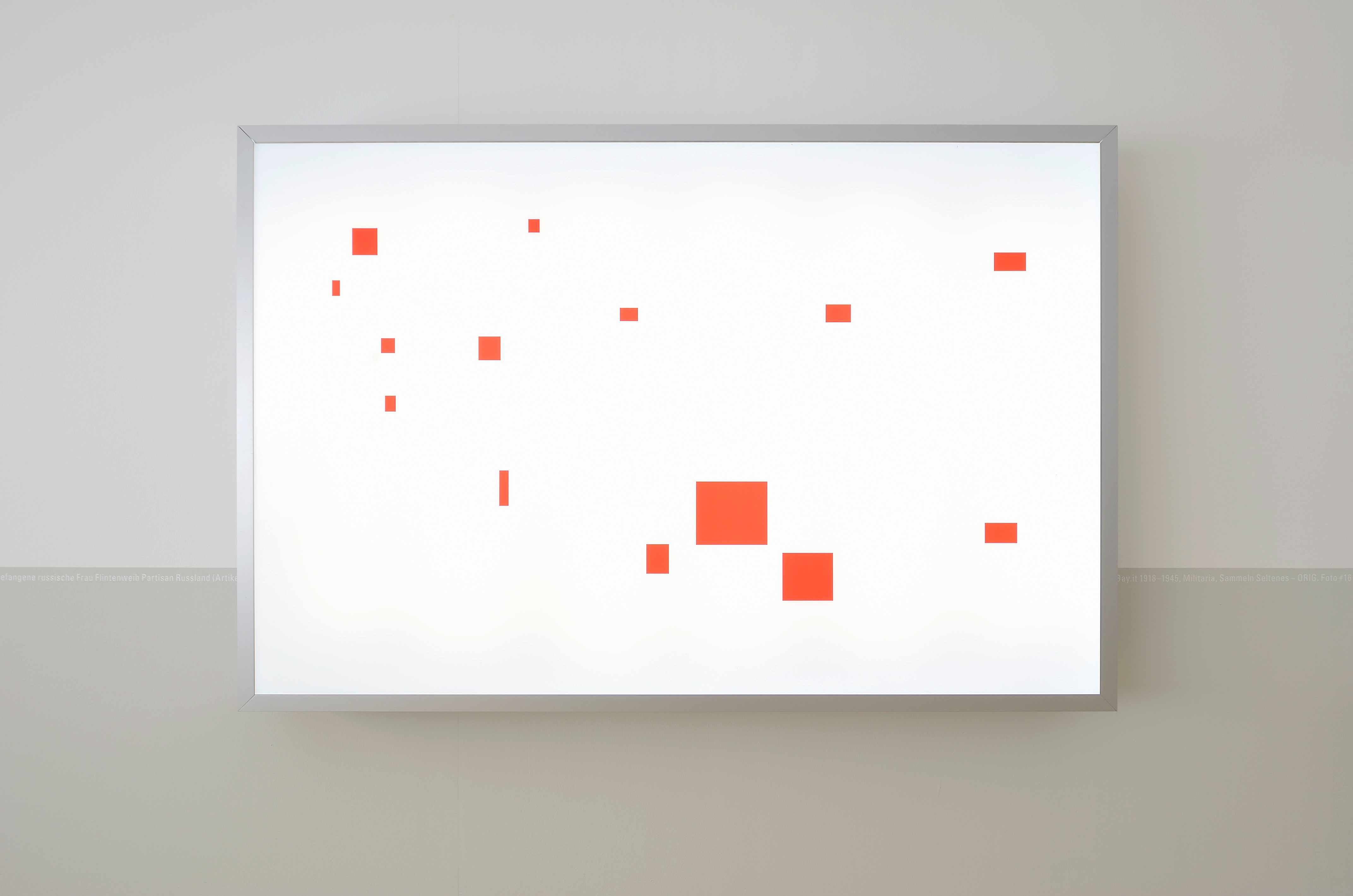

One example: In one of my most recent works, I subtracted the copyright marks from WWII photographs sold on eBay. The pictures were made by German soldiers on the Eastern front and show all sorts of war scenes. The more violent, the more expensive the photos are. eBay vendors add copyright signs to affirm their property rights, and also to cover representations of war crimes, swastikas and other illegal content. In my work, I’ve subtracted the photographic images and left the copyright marks as they were. They represent the original photographic picture seen from the angle of their existence as digital commodities. This is their contemporary form of circulation and movement. Yet, in a negative and subtractive way they retain the traces of the resistance of the persons originally shown in the pictures, mostly captured female Soviet soldiers, who were fighting against the Nazi invasion. Those women constituted one of the groups who were to be immediately killed after their capture; they had no chance of survival. So in some cases, a very abstract form of their negative imprint is preserved.

These are their portraits in 2010, under the condition of digital capitalism, and I’d argue that these are documentary images, because they show the reality of the contemporary movement and dispersion of the original photographs.

RH Aside from being documents of our contemporary digital reality, the compositions of your EBay works are unmistakably reminiscent of abstract paintings. This brings up all kinds of issues. For one, I am tempted to say the works have the effect of re-contextualizing abstract painting, as seen in its 1950s heyday, as being a kind of blunt instrument of forgetting – something I hadn’t thought about before. This idea makes sense, I suppose, if you consider the postwar ascendency of American culture as being somehow amnesic in intent. Your EBay works also evoke ideas about the dematerialization of the artwork. Conceptual art prefigures the regime of the virtual we now live in. Abstract painting also fits within this narrative: abstraction prefiguring abstraction. In your essay In Defense of the Poor Image (2009) http://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/94 you note that “dematerialized images…[are] a legacy of conceptual art.” You write very persuasively about the importance of the degraded image; and of its capacity to enact a form of “resistance against the fetish value of visibility”. Given that relevant precedents for these works are abstract painting and conceptualism, I am curious to know, what form do they take when presented in an art gallery?

HS I hope that, in a gallery, this work might inspire people to think about the form what is considered sublime takes: purely formal and self-referential art. Because this installation may look every bit as fetishist as if it were Art with a capital A; but it is not – it is found material from the junkyards of the web, powered by a dubious digital scopophilia. It is actually copyrighted military porn; if not worse. So what is the relation of this type of mobile image to abstract art?

In his book The Century (2005) Alain Badiou writes about the “passion for the real”, which according to him, dominates the 20th century. This passion is characterised by a desire to tear away the veils of mere appearance and deception and to uncover the real essence of the thing under investigation. Politically, this unleashes a huge amount of paranoia against people who are not deemed pure enough or traitors of a cause. The passion for the real is not only a motor behind many of the massive purges and maybe also ethnic cleansings of the 20th century (there are other motors as well), but as Badiou argues further, it can also be detected in abstract art works (his example is Malevich). These works evacuate the frame of everything deemed superfluous, they literally purge color and form. It is quite interesting to think about this link between the genocides of the 20th century and abstract art, both aiming for an essence, a purity to be achieved on the one hand by elimination on the other by subtraction (obviously, and Badiou insists on this: by completely different means).

In the case of the eBay work, both somehow collide: what looks like a sublime and completely self-referential minimal artwork is actually a coincidental trace of war crimes, its price tag, if you will.

RH Could you speak a bit more about the relationship of your practice to the concept of the poor image and the image in motion?

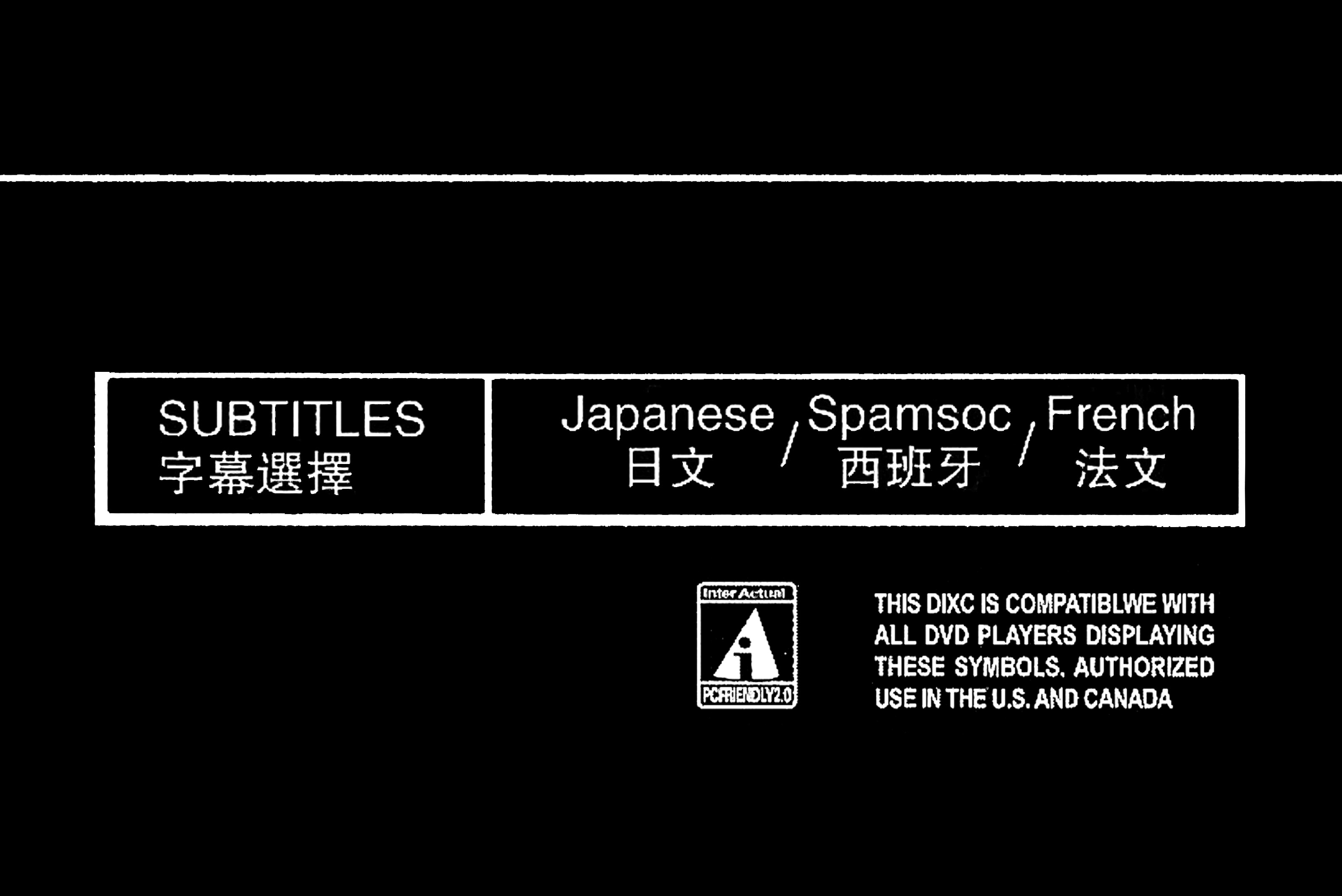

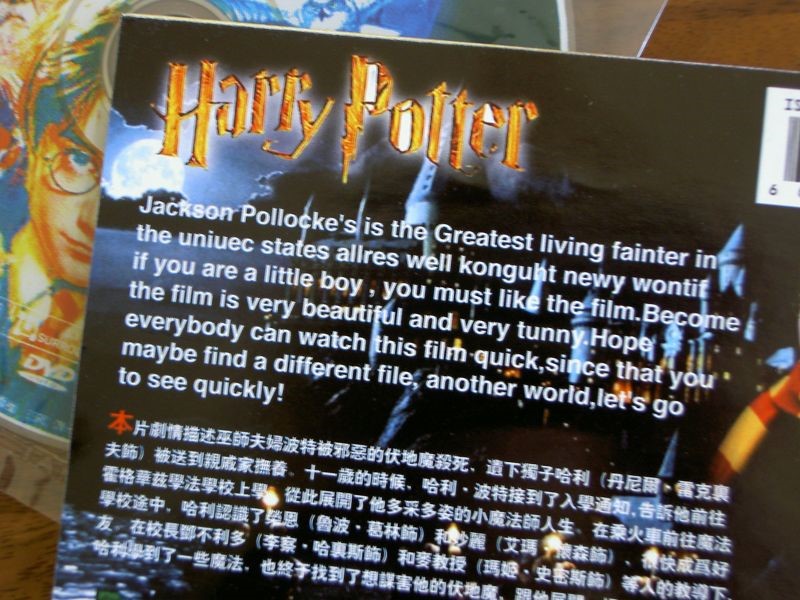

HS I have been interested for a long time in traveling images, in the ways in which their meaning and appearance changes. These, for example, are samples of pirated Chinese DVD covers on which a new peculiar language emerges. This language is called Spamsoc, as you can see.

Spamsoc is generated by online translators, automatic scanner recognition tools, and travels on the back of pirated DVD’s. It exists in many countries and knows many local dialects.

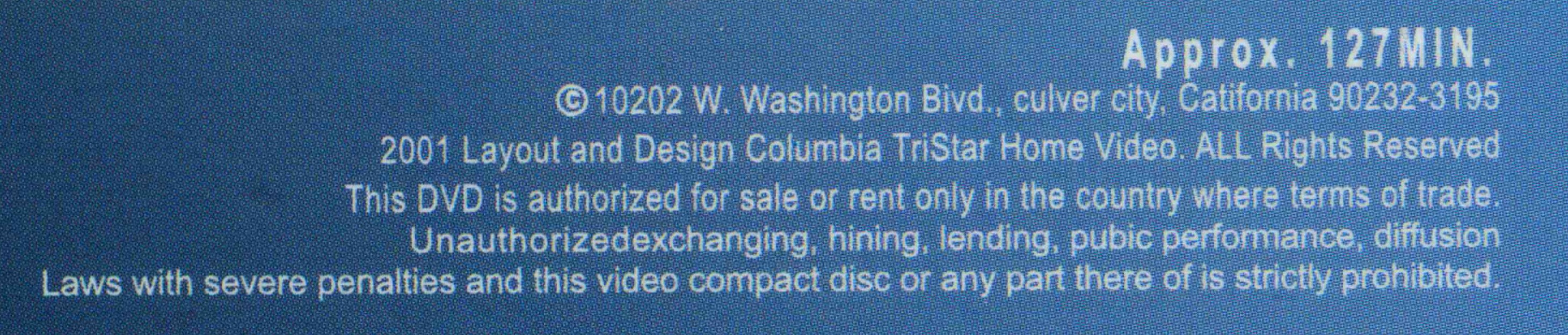

Probably it emerges late at night on the desktops of digital shockworkers, who compress, rip, and transfer audiovisual data and create covers and blurbs on the side. It is a language that is created within multiple conflicts, most of all conflicts over copyright. This is also why it is a broken language. I see it mainly as a great improvement on the English language and proof of how backwards we are, because we are not able to fully decipher this language from the future. Spamsoc’s multiple neologisms express disagreement over the ownership of audiovisual content, the domestication of translation and other aspects of digital shockwork. I love the automated “Freudian” slips (which are no longer Freudian of course), which lay bare the digital unconscious of the period. Take for example this genius term “the pubic performance”, in the jpeg below.

In one decisive blow, it expresses the decline of the public sphere; the demise of traditional cinema and its replacement by private home cinema; the transformation of an always illusionary public defined by rational deliberation into a pubic sphere that thrives on spectacle, shock and scandal; as well as the performative character of these elements of the private running amok in public…

The pubic performance is the production of self on countless webcams, endless chatter on social media, confessions about trauma on Youtube, post-oedipal drama on morning TV.

RH I love the precision with which you have been able to pinpoint these one details, Spamsoc, the pubic sphere, which are fantastically emblematic of Globalism. I have read your explanation, understand it, and yet I still do not know what Spamsoc is. As you say, we don’t understand it because we are not from the future. It’s also like a spot on the far horizon, the arc of the future, the jet plane of Globalism flying over our heads to a place we will never visit. I am interested to know how Spamsoc figures in your work? It’s a file you made from a scan of a pirated DVD that you sent to me by email. As such, it embodies your interest in what you call “travelling images”. This brings up a question for me: if images travel do they ever come to rest, and if so in what form? In turn, this opens up onto the bigger issue of how a digital file relates to what we traditionally think of as an artwork? I realize this may not be the right question to ask, because I can see your work exists as a kind of matrix of text-plus-image-plus-gallery shows. Still I would like to focus on this problem because it touches on much bigger questions. It is hard to credit a digital file as a “real thing,” which points to what I see as the epoch-defining cultural confusion about what is “real”; or maybe more specifically: what is truth and what is fiction? The examples of this are legion but can perhaps best be summed up by the fact that “reality” itself has become a genre, one that “everybody knows isn’t real (sort of).” Can you talk about this problem in relation to your work?

HS Very concretely. I’ve written a text and made and interview with Jon Solomon, a translation theorist, who is based in Taiwan. Both deal with the production and circulation of Spamsoc. I also made a file, which documented those DVD covers visually, though I do not consider it art. Generally, I think this question about whether something is art or not is a bit overrated – because essentially the question is mostly about gatekeeping and declaring that certain types of art shall be excluded. Paradoxically the non-art thus becomes essential for defining and sustaining the art with a capital A. But obviously, there are works with more or less formal concerns, or even different formal concerns, which may or may not be challenging enough to create a productive uncertainty (which might be my provisional definition of art: emphasis on productive). It’s about the question of form in information, the relation between both. For me, pure form is just as uninteresting as pure information.

So, can a digital file be art? Why not? Depends. It’s more important though, that there is something challenging, motivating and unpredictable about its relation it poses between form and information.

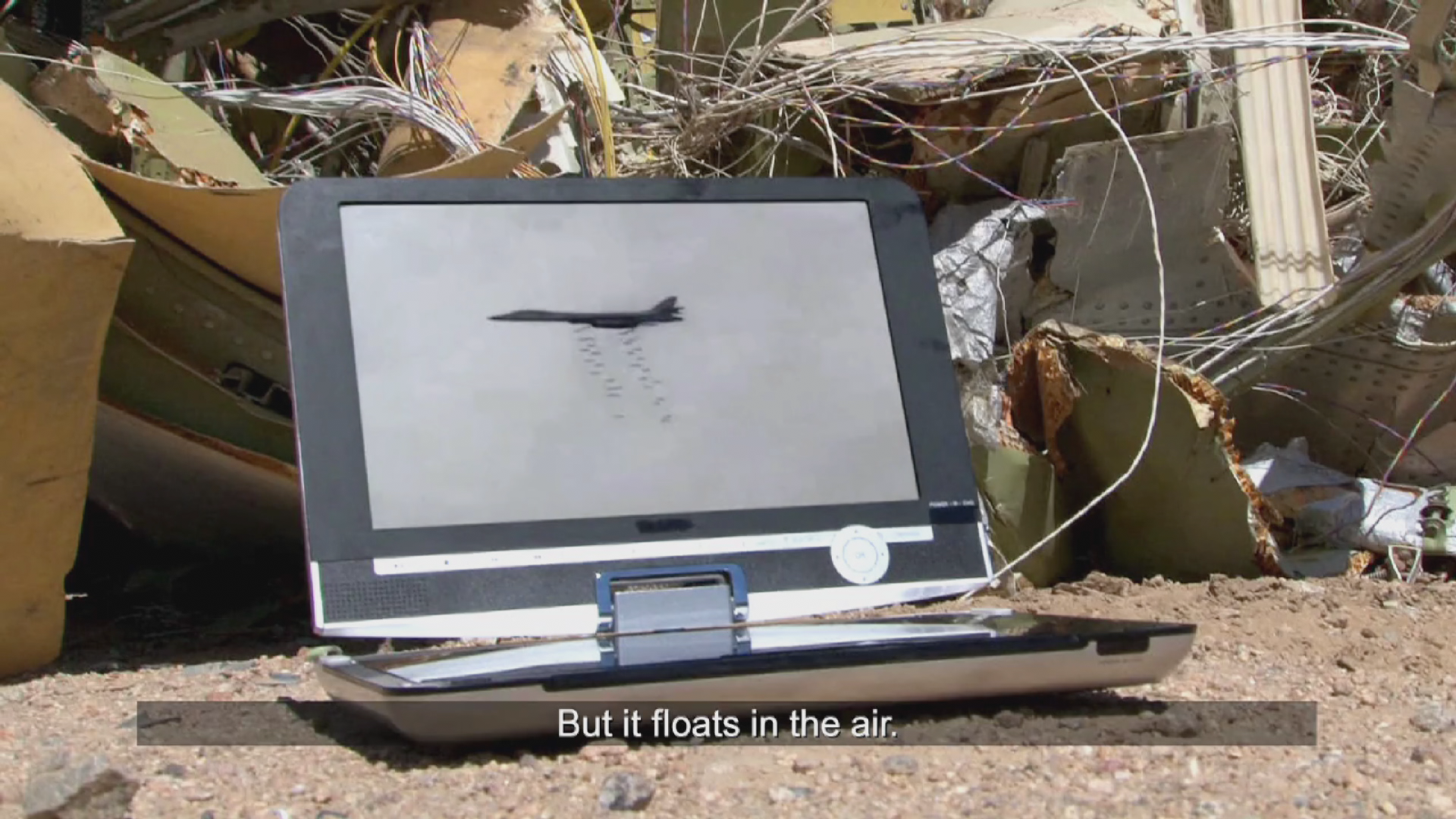

Is a digital file a “real thing”? That’s another question. It certainly has a reality on the material level – the level of electricity and material support. It is certainly also very much connected to reality through its coding and format. A VOB file on a DVD is pretty real, as it is tied to different networks and markets of raw materials, in this case, for example, metals and plastic, both of which are often recycled; not to mention hard disks, burning devices or other storage media. All these have the same level of reality as the material support of a photograph, or film stock. Thus there is often a history of the object, or objects involved in the storage, production and processing of a file. I made a work recently about recycling of aluminium from former military planes, and how this becomes the material support for DVD’s.

I also have extensive notes for a history of glass in media, of the use of glass fiber cables, glass as a metaphor for transparency and communication. Glass is also one of the sensories of the social. Broken glass refers to destitution or insurrection. On all these levels – and surely, the art gallery with all its institutional codings can be included with these other material supports – we could perform a material reading of the carrier medium, but also of the social histories of encoding and transmission. Obviously these are also tied to issues of copyright, audiovisual property and the social struggles around it. This is real enough for me; or perhaps if it isn’t, it’s still interesting enough. The question whether the content of the file relates to reality or not is another question, which is ultimately undecidable.

But yet again, there is always a perspective, which looks at the reality of the fiction, if you like, its infrastructure, so to speak. That is, in order to get confused about fiction and reality there needs to be a huge apparatus already existing in reality, which consists of hardware, software, institutional frameworks. Like in the movie Inception – in order to create the confusion about dream and reality you need a huge infrastructure in the first place. Cables, medication, game architecture; take this away, and the fiction (or in this case, dream) collapses. Same goes for the cultural industries, or perhaps more precisely the military-entertainment complex. It is the material base for all our confusions about reality, its matrix and it is very real.

So there is always – I think – a substantial degree of material reality to all digital things. But it may not even be so interesting to figure it out – perhaps it’s more interesting to explore the new realities created by fiction, digital or not. There is a constant transfer between reality and fiction, but as I see it, it mainly consists of misunderstanding, faulty imitation and mistranslation. People (like the urban guerilla in my video November (2004)) try to imitate fiction films; they fail, but produce new realities. It was Hannah Arendt, who said, that that ultimate creative force in politics were lies. Who could deny that the lie about the existence of WMD´s in Iraq created massive new realities?

Originally published by Animate Projects July 7, 2011