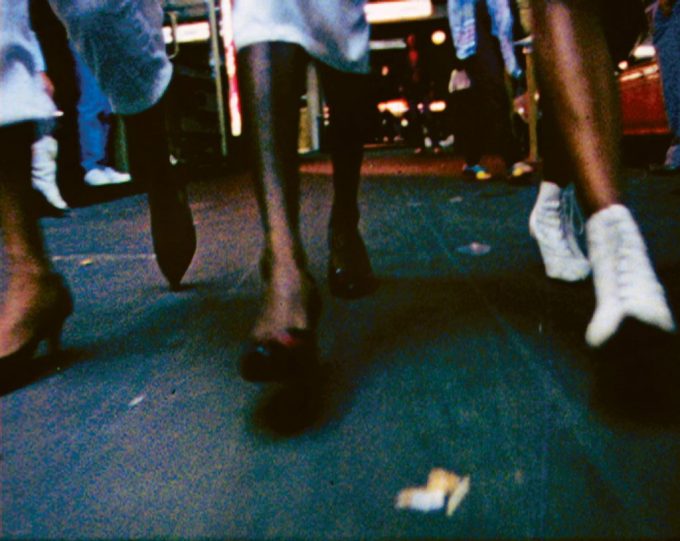

Allison Hrabluik, video still from “The Splits,” 2015. Image courtesy the artist.

Studying the human body in movement is a constant in Allison Hrabluik’s work. Starting first with hand-drawn animations, then making more abstract films derived from tracing figures on YouTube, the artist has most recently worked with real people to make her short film, The Splits (2015). The beguiling piece that results suggests another constant in the artist’s practice: an intuitive ability to use the things she works with — often random, dissimilar — to tell a story wrapped up in the artwork’s process.

With The Splits, Hrabluik constructs an unlikely portrait of everyday life in British Columbia by focusing on people performing a skill or hobby they are passionate about — from sausage-making to Afghan Hound-grooming. The desire to practice and get better at something, whatever it may be, connects the film’s subjects, and this includes Hrabluik and her facility for filmmaking. The artist told me she followed no strong rule about who would be included in the work. Instead, she found participants through an organic process, one that combined on-the-ground research with referrals from friends. She pulls it all together according to an intuitive logic both enigmatic and highly persuasive that makes clear the skill the artist brings to the project.

Hrabluik beguiles through the trickery of cinema. The work’s greater subject is the idiosyncratic space the film constructs and the role viewer perception plays in its making. A tightly focused camera frame makes us aware of the film’s synthetic space. Reinforcing this impression is the location where Hrabluik shot The Splits, a community center in Surrey, British Columbia. A typical setting for many of the activities the artist depicts — a tap dancing rehearsal, for instance — by using it to bring together a disparate range of such activities Hrabluik creates an enhanced but denaturalized context for her subjects. This approach is made clear from the film’s opening frames when the viewer receives partial pieces of information that become more intelligible as the film progresses. Sound from each scene carries over into the next, helping to establish the broader coherence of the work.

The Splits takes place within the white space of a rehearsal hall, and also in the world Hrabluik creates. This opens her work up onto a wider conversation about the use of art as a tool for scripting reality, a contemporary preoccupation that extends from the lowest forms of pop culture to the high art aspirations of literary autofiction. In her method of using real-world performance to capture unexpected, composite effects, Hrabluik’s film shares a lot in common with these tendencies. I spoke with the Vancouver-based Hrabluik this March about her artistic process, the logistics of filming The Splits, and where her practice might lead next. Following a presentation at Kassel Dokfest, in Kassel, Germany, the film is currently on view at SFU Art Gallery, Burnaby, BC, with an upcoming screening at Images Festival, Toronto.

You’ve described movement as being a unifying factor in your works, can you distill what’s of interest to you there?

Prior to making The Splits, I had been making narrative video works, and found that I didn’t know what kind of story to tell anymore. When it came time to write a new script, I could focus on almost anything, so how should I make a selection?

I was also reading a lot of fiction, and began to notice the similarities between many of the books on my shelf. They were wildly different in content, but similar in that they all describe how we manage, or don’t manage, the situations we find ourselves in. I wondered if this internal struggle could be distilled into something visually. Perhaps through the ways we physically move through the world. I began creating movement-based scripts as alternatives to narrative scripts, in an attempt to reveal a character instead of telling a story. To do this, I worked with a composer and a choreographer and began to trace films, looking for different ways to make things move.

You also made works by tracing videos found on YouTube — taking a video and choosing it for its movement. You mentioned this was the provenance for The Splits?

Yes. I was looking for videos to work with, and came across a group of young gymnasts online who record themselves performing in their living rooms and backyards, and post the videos to Youtube. The footage was strangely captivating but because they were teenagers I knew I couldn’t ethically use their images. So I started meeting with gymnasts and dancers here in Vancouver. I began videotaping them, planning to use the footage to trace their forms, but soon realized that altering the images wasn’t necessary. There was instead something in the connection between performers that I wanted to follow.

I contacted as many people as I could find who I thought moved in interesting ways. I started with gymnasts, a hula hooper, and weightlifters — athletic ways of moving. To round this out, I considered other ways of performing, like opera and burlesque, amateur music, and how we move everyday at work and with animals. I also incorporated elements of our lives that lean towards the grotesque — the salami makers and the hotdog eater. The absurd is linked to our everyday as much as the transcendent, which is often what we look for in physical excellence.

And you knew all the people?

I know a few of them. Barbe Atwell, the hula hooper is a friend, the tap dancers I saw tap dancing on Granville Island, and the dog trainers I found online through the Afghan Hound Society. Others, like the skippers, gymnasts, and weightlifters I contacted through their coaches, who put me in touch with people they thought might be interested. Often friends recommended people.

I began to notice that if there’s an action people do, there’s a team around it. For instance, I was thinking about skipping, fencing, competitive eating, dog training, birding, etc., and found communities for all of them, each with their own language, skill set, and measures of success. In this project, art and filmmaking became only one activity among many, and I enjoyed that opening up.

That brings me to another question. I noticed in the bibliography that accompanies your show that it includes the category Scripted. What’s the connection?

Melanie O’Brian, the director of SFU Galleries and the curator of the exhibition, asked me to compile a bibliography of books that formed my thinking around The Splits. She knew that literature is often a starting point for my work. Scripted is a section of the bibliography, and includes The Species of Spaces and Other Pieces (1974/1997) by Georges Perec, who works with writing constraints, and also the catalogue Yvonne Rainer: Space, Body, Language (2012). Rainer uses a lot of annotated scores to direct movement in her choreography.

Okay. Because that brings up a whole world of ideas that are relevant to the current moment. For instance, the idea of autofiction associated with the Norwegian writer, Karl Ove Knausgaard.

I’m not familiar with the term autofiction, but think I know what you mean. I read the first book of My Struggle (2012), and enjoyed it. Other books in the bibliography for the exhibition, like Marguerite Duras’s The Lover (1984/1985), bill bissett’s work, Elizabeth Smart’s By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept (1945), I believe fall into that category. I’m also interested in nonfiction that has literary qualities, which for me begins to read in similar ways. Like Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974), and Sharon Butala’s Perfection of the Morning (1994).

What some of these works share is a thinly-veiled allegory of self-love and self-destruction as two sides of the same coin. Sometimes describing this in a cool voice, other times with unapologetic effervescence. It’s the effervescence that spills into The Splits.

This makes me wonder about how scripted your works is? Is it scripted?

The selection of the cast was carefully arranged, as was the location of filming. We filmed at Sullivan Hall in Surrey, a very active community center. The events that happen at Sullivan Hall on a weekly basis are not far off from what happens in The Splits. The weeks before we filmed, the hall hosted a wedding, a bird sale, a rock and mineral show, an auto show, yoga lessons, and dog training evenings.

Creating the situation became the script. I trusted that once the cast and location were in place, something interesting would happen. During filming, I asked the performers to perform whatever they wanted. We filmed everything, and I made a lot of decisions during the editing process.

The framing is so important. When the film starts, it’s the tap dancers. Then it’s the hula hoop woman, but the way you frame it, there’s some degree of ambiguity. You are suggesting there is an equivalence between the frame and the stage, and that creates the space of the film. Were you always trying emphasize this tight framing when shooting?

I was interested in the similarities between the different actions performed. The motion in the close-up scenes of the hula-hooper is echoed in the close ups of the gymnasts and weightlifter. By initially hiding the particular activity involved, I could focus on their shared qualities. In the end, it’s curious to know that it’s a hula hoop, a dumb bell, and balancing exercises that create such erotically-charged motion, but it’s not really about the hula hoop.

Right. I guess that’s what you give to the viewer is this puzzle to work out about what’s going on. Why are these things together and what connects them all? I think you can intuitively understand that it’s pretty open but I think you are also very aware of the frame.

I needed a frame, I did. I tried not to have one. I tried to film in everyone’s individual spaces and it didn’t work. So the hall and the stage and the close cropping become devices that connect what might otherwise be a random grouping of people, isolating and highlighting their actions. The neutrality of the hall is important. While it has the character of a space that is well used for performance and celebration, it also shares the neutral characteristics of an exhibition space, allowing us to focus on movement over setting.

Obviously you are able to work with these people because you have that sensitivity to what they need to feel comfortable, and to perform. It’s very naturalistic, that was another point I was going to make …

The process was comfortable, and this was important. I met with everyone individually before we filmed, to describe the project and answer questions. Once they arrived at the hall, we spent several hours filming each group. This gave them time to become comfortable in front of the camera. A feeling of naturalness also happens through editing. I searched through hours of footage to find moments where the performers were unguarded. Much of the scripting you asked about earlier happens there.

It’s not a documentary.

I think it intersects documentary and fiction. The performers are performing themselves, but the situation that brings them together is constructed. I’ll continue to explore this intersection with other subjects, leaving movement behind for a while.

Do you think about directing? Will you be making a more scripted film in the future?

Yes, I’ll certainly experiment with a more scripted approach. That might involve writing scripts while leaving room for improvisation.

Rosemary Heather

This interview originally appeared in Momus, MARCH 29, 2016.

More information about Allison Hrabluik here.

Dynasty Handbag, photo: Charlie Gross

Dynasty Handbag, photo: Charlie Gross