By Rosemary Heather

Rodney La Tourelle, In the Absence of Unambiguous Criteria was presented at Program, Berlin, Winter 2007

This text was orginally published in Von Hundert, Berlin, Spring 2007

Art writing I’ve done since the early 2000s, orginally appearing in a range of online and print publications internationally.

By Rosemary Heather

Rodney La Tourelle, In the Absence of Unambiguous Criteria was presented at Program, Berlin, Winter 2007

This text was orginally published in Von Hundert, Berlin, Spring 2007

—Abolfazl Ali, head of Chehr-Abad research group

“To open the doors of the Atomic Theatre your eyes have to open up like a vast reservoir of water falling from another planet. Once the mind has turned inside out, the springs of time will emerge as the centre of your cognition. The Atomic Theatre takes its pulse from the antimatter of materials that exist in an unknown dimension called invisibility.”

—Ron Giii, The Atomic Theatre and The Dictator’s Opera

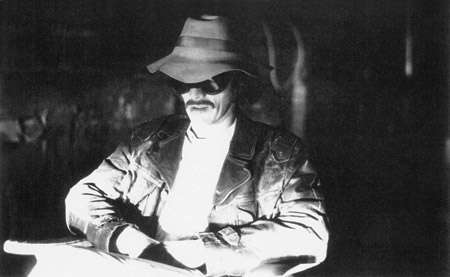

Ron Gillespie

Things change. A banal metaphysical statement worth reflecting on. This is especially true if you have the materials at hand to give substance to the idea. The work Ron Giii has made over the course of thirty-five years provides the perfect vessel for these considerations; in Giii’s oeuvre you can see what changes and what stays the same, much as you can in a biological body over time. This is also to say that art provides an excellent answer to the question, Where are we?

If you ask Giii, the continuities that both defy and define the present are “the antimatter of materials that exist in an unknown dimension called invisibility.” Even in this fragment from the artist’s writings there is so much to discuss, as in his work as a whole: mine deep and you will discover riches.

Ron Giii

Giii’s work presents itself at the place where the invisible meets the visible; another example of this is theatre, which like visual art takes place within a framework, or proscenium arch. As in art, theatre is the forum where antimatter becomes visible, precisely because the primary consideration of art is form. In Giii’s case, artistic form and the forum of its presentation converge in a way that is especially distinctive. Giii’s full sentence: “The Atomic Theatre takes its pulse from the antimatter of materials that exist in an unknown dimension called invisibility.”

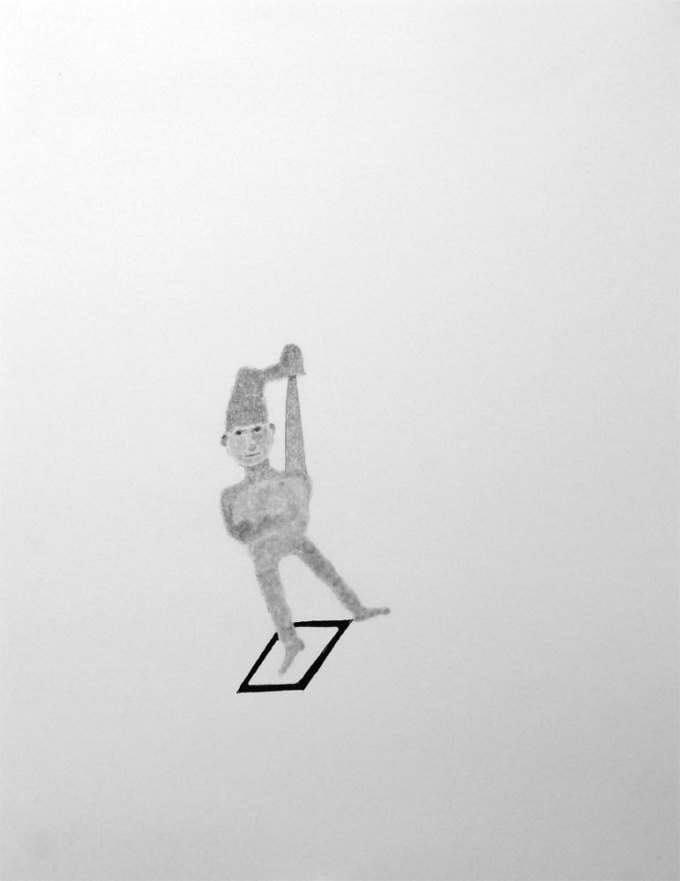

This is a quotation from a text written by Giii to accompany a show of his drawings in New York in 1986. A wholly coherent statement about his oeuvre, the text and the show provide a good pivot point on which to consider the stages of his career. What began as performance continues as drawing, all of it taking place within the conceptual framework of theatre. In Giii’s view, theatre formalizes the process of becoming that is all of our lives. Like us, the figure within the frame or on the stage looks outward, seeks a connection with others and beckons to an audience more often than it turns its back to the world. The proscenium, like the page, presents a threshold of possibility just waiting for the moment of its random apprehension.

Uncle Ron

Looking at Giii’s art, one understands that the simple encounter is his fondest hope for it; each work provides this encounter, fulfilling this desire with imperceptible ease. The drawings live and shimmer with unimagined sensitivity. In The Atomic Theatre, Giii speaks about the figures in his drawings as real people, “laughing and hiding from me as if they had their own reality.”

Giii was already active and engaged in the Toronto scene when he was a student at what was then the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD), in the 1970s. It was a cultural moment in which the bohemian sectors of society were alive with dreams and ambitions that are difficult to fully access today. Giii’s early works provide a way in. At the time, “live art” was a fringe pursuit. In 1978, Roselee Goldberg, writing in the first authoritative study of performance, noted that it had only recently been accepted as “a medium of artistic expression in its own right.” Like other practices in the visual arts in that moment, it was a hybrid—theatre or sculpture and dance—newly unbound from traditional constraints. In common with much that happened post Minimalism, performance art found its possibility in the context of art itself.

Jimmy Algebra

Pervading the era in which Giii first started working were the powerful cultural tendencies of political radicalism and lifestyle utopianism, not to mention the commercialism of these trends in the pop-cultural mirror, with its attendant distortion. Artistic disciplines intermingled to electric effect. Along with freedom from medium specificity and craft was an embrace of ordinary things as subject matter for art, including garbage and noise—the incidental art of John Cage and Fluxus—and, above all, people. The Happenings of the 1960s included audiences reimagined as paintings and sculptures, with the gallery as frame. In this context, real human bodies—frequently naked—had an incredible impact.

The shock produced by a simple encounter with a human body—naked or otherwise—and the things you could do with it, was a basic element in Giii’s art at that time. The experience could result in a psychological and sometimes physical violence. While both were still students, Kimo Eklund and Giii created the performance entity SHITBANDIT. Giii has said,

We used the name to shatter the very conservative milieu surrounding OCA . . . we did Christ on a pair of two-by-fours with microphones placed out in the street, and a used Volkswagen where males and girls got it on and they were surrounded by porn mags.

Johnny Pizza

A site for many of Giii’s early performances was the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC) in Toronto, one of Canada’s first artist-run centers and one with a short, explosive history. Ever more and more radical in the theoretical and political platforms it promoted, CEAC eventually lost its government funding. Its many provocations gave birth to a notoriety that is increasingly obscure—and that appears to have little relevance to the activities and self-image of the Toronto arts scene today.

As part of a group of artists associated with CEAC, Giii traveled and performed extensively in Europe and the United States. A 1976 tour, for instance, took the group to Sweden, Germany, Italy and Belgium. Communicating with each other via the postal system, among other methods, rather than the Internet, they were part of the first globalized artists’ network, made possible by the dematerialization of artwork. Dot Tuer comments on the intense schedule of activities carried out by CEAC. She has noted that “during 1976 and 1977, there was literally an event held at CEAC every night of the week.” As with everything, the moment was fleeting; as Giii wrote, “The performances were wild like animals who were going extinct.”

The General

In her fascinating and very thorough scholarly essay on the history of CEAC, Tuer notes the influence of Hermann Nitsch and the Vienna Actionists on the kind of performance work Giii, SHITBANDIT and others did at CEAC.1 Self-exposure, transgression and ritualized actions formed a common thread, the goal being to orchestrate a moment of “raw” experience for audience and performer. Informing it all was the idea that confrontational art stripped away layers of falsity in consciousness and social interactions, and the naked individual in the gallery promised a return to Rousseauian innocence and/or political consciousness or some combination of the two.

While the Vienna Actionists were motivated by the desire to expose the incipient societal guilt stemming from the not-so-distant (Nazi) past, Canadian shock performance tactics had the broader target of exposing the individual’s complicity in a generally corrupt society. Giii: “After reading texts on the destruction of nature we adapted the wild behaviour and hence we entered the world of dominance, force, power and abuse.” This focus in Giii’s work continued into the 1980s in the film Taste, the only surviving example of his work in Super 8. In Taste, which was shot in a garbage-strewn alley for about $100 in 1984, Giii and Darinka, his female accomplice, subject each other and themselves to a series of ad hoc actions. By turns emotionally disturbing and theatrical, even Dadaesque, the performers’ actions have quasi-sado-masochistic overtones, but Giii’s intention in the film was to do more than shock. He makes this clear in the soundtrack, which he narrated spontaneously in a single take after the fact in complement to the film’s continuous improvisational performance. “The artist is a fascist,” Giii intones many times throughout the film, questioning the power dynamics inherent in the artist’s relationship to the audience and to the work of art. Enacting a theatrical sado-masochism in the film, Giii indicts himself, but as with the doctrine of original sin itself, this is only to declare that he is part of humanity.

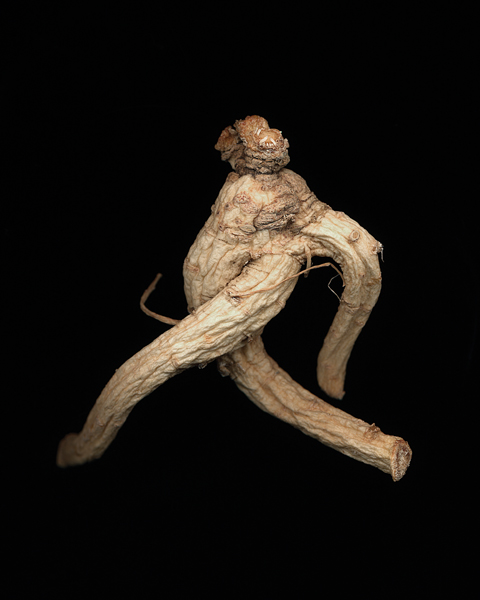

Hegel’s Salt Man

In his later work, Giii’s investigations into the dynamics of power gave way to openness and vulnerability. The figures in his drawings are always tender and are rendered with the lightest of touches, like a mere breath upon the page. Frequently also present in these works is a proscenium arch; figures float inside a box or within intersecting lines that delineate geometric space. Together, the lines and the figure represent a new naked self, one that grapples with and must survive life’s intractable circumstance and that does so with moments of joy and lucidity. Another quote from Giii: “Each instance of conception is a view of a theatre that has no words nor semblance of a rational world with all its contradictions and confusion.” Combined, the early and later works compose a biographical “before” and “after,” that corresponds to Giii’s experience with bipolar disorder; the drawings belong in the “after,” which continues to this day. More striking, however, is the work’s extraordinary coherence and wholeness, as if all of it were of a piece, antimatter that was once and will be again invisible, that is available as a point of contact in this moment and yet is just passing through.

By Rosemary Heather

Epigraph Ron Giii, from his text produced to accompany the exhibition The Atomic Theatre and The Dictator’s Opera, 1984–86 at 49th Parallel gallery, New York, 1986.

1. Dot Tuer, “‘The CEAC was banned in Canada’: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” in Mining the Media Archive: Essays on Art, Technology, and Cultural Resistance (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005), which can be purchased here.

This text was originally published to accompany the exhibition I curated, Ron Giii: Hegel’s Salt Man, presented at the Doris McCarthy Gallery, University of Toronto (2007) and Carlton University Art Gallery (2008). The catalogue Ron Giii: Hegel’s Salt Man: writings/works 1975-2007, featuring essays by me and Eli Langer, can be purchased at Art Metropole.

Andrew Patterson wrote a review of Hegel’s Salt Man you can read here.

Deborah Margo wrote another review of the show in Bordercrossings 108, but its not available online.

A version of this text appeared in Hunter and Cook No. 8.

Ron Giii is represented by Paul Petro Contemporary Art, Toronto.

A couple years later, I visit Second Life again, this time with a more ‘legitimate’ destination. I am going to RMB City, a project of the Beijing-based artist Cao Fei. Still my experience is much the same. Where is everybody? I am suffering from a disjunction between real the virtual, a dynamic Cao Fei had explicitly set out to explore. My experience helps to shed light on the problem, but it’s of the unintended sort. If my navigations through the world of Second Life are cumbersome and alienating, it’s because I have a sub par computer. It’s an issue of processing speed. Inadvertently perhaps, Cao Fei’s ambitions in Second Life provide a metaphor for the looming dilemma faced by the West. We are lagging behind but lack the drive needed to overcome this predicament.

Disjunctions between the real and virtual worlds, often unintended, also dominate the Residency in RMB City project. Because it is located in the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in the Toronto suburb of Don Mills, the Gendai Gallery is somewhat hard to get to. With this exhibition Gendai curator, Yan Wu, puts the venue’s peripheral status to good conceptual use, proposing a show that can be, in part, accessed by computer. Working with the artists, Adrian Blackwell, Yam Lau and the collaborative duo of Judith Doyle and Fei Jun (known as GestureCloud), Wu creates an exhibition that combines a gallery presentation with digital artworks created for Cao Fei’s Second Life property.

Made up of an amalgamation of references to Chinese architecture, RMB City features the Herzog and de Meuron Bird’s Nest along with shiny skyscrapers, motorways and sidewalks, warrens of small shops selling take out food and the like, all of it organized around the central structure of the Forbidden City, Beijing’s Imperial Palace, which dates from the Ming Dynasty. Although Cao Fei promotes her project as a platform for artist collaboration, miscommunications meant that Wu found her initial proposal to create an artist residency in RMB City rejected by the artist. Further communications remedied the situation; as of press time, the artists are soon to begin moving their projects to the Second Life location. In recognition of the changed status of the project, this second phase will now be termed Intervention into RMB City. A publication about the project, called From Residency to Intervention will be published in the spring.

In the Gendai gallery, Blackwell presents Lóng Sùshè (Dormitory) (2011) a plywood maquette of a workers’ dormitory proposed for RMB City. Trained as an architect, Blackwell has lived in China, teaching architecture there at an offsite campus of U of T. With Lóng Sùshè he provides infrastructural context for Cao Fei’s metropolitan fantasy. An interest in sculpture as a platform for public discourse has been the long term focus of Blackwell’s practice. Referring to an actual dormitory in the industrial region of Shenzen, one that is continually being built in an effort to meet the growing demand for worker’s housing, Lóng Sùshè, helps to clarify certain questions that will emerge along with China’s growing economic dominance. What kind of public will China’s new global order create? How easily do traditions of the West translate, and are they even relevant? The notion of a public sphere is amongst the highest ideals of a functioning Democracy, but it’s not clear how it will figure in a country that has little in the way of democratic traditions as they are known in the West.

Writing about the legion of workers that power the engine of China’s economic expansion has become a journalistic trope in Western reports about the country. China’s nineteenth century industrial conditions are a subject of some fascination in the West. Such reportage helps provide a salve for the conscience of those enjoying the products of cheap Chinese labour. Judith Doyle and Fei Jun’s GestureCloud (2011) uses the space of Second Life to rewrite this narrative, to great critical effect. In place of the whole, but nameless, Chinese worker, the artists create a virtual inventory of the gestures factory employees are forced to repeat, ad infinitum, when doing their job. Based on video documentation of the duties performed in a printing factory in Beijing, GestureCloud represents these workers in terms of their real world effects. This distillation by the artists’ creates clarity: like everybody, really, in global economy, the factory workers are mere nodal points within a vast system — or to borrow a 19th century metaphor, cogs in the machine. As with other multi-user online environments, Second Life has a real world economy, money changing hands in the form of Linden Dollars (San Francisco’s Linden Labs is the company behind the site). For the RMB City stage of the project, these gestures will be available for purchase via a vending machine in Second Life, the animations being useful presumably for avatar-related Second Life labours. Gesture Cloud’s ultimate ambition is to return the money they make back to the factory workers in Beijing.

One translation of RMB City is Money Town; a mordant commentary on the breakneck pace of economic development in China, Cao Fei’s project also creates a narrative for the transition China is currently undergoing — and the implications it has for the rest of the world. Anyone with a computer and an internet connection can use Second Life; the language of software is more or less universal. With Princess Iron Fan (2011), Yam Lau gives expression to the heterogeneity of elements from which this new Global culture is being constructed. Princess Iron Fan is character from a Chinese folk tale, adapted for a film of the same name, which was the first animated feature film made in China, in 1941. Lau adopts the figure of Iron Fan as it appeared in the 1941 animation for his Second Life avatar, but with important alterations. Presented in pleasingly anachronistic black and white, the avatar is given certain ghostly characteristics. It is visible from the front but not the sides or back; the artist slyly attributes vaporous qualities to a thing that already has no substance. In the gallery, the projected animation appears from time to time, mimicking the avatar’s movement through the virtual world; in Second Life, Princess Iron Fan is programmed to similarly ambulate around. However, she never appears in both places at once: Princess Iron Fan is perpetually destined to exist on the threshold between the virtual and the actual. In metaphorical terms, the virtual animation of a Chinese folk hero points to the changed cultural landscape that will characterize the 21st century – an expanded world no longer necessarily bound by Western ideas or traditions.

By Rosemary Heather

Residency in RMB City is a project of Gendai Gallery, Toronto.

This text originally appeared in Bordercrossings, Issue 118.

The centerpiece of the show is ‘Every Part From a Contaflex Camera Disassembled by the Artist During Winter, 1998’ (2006). Like a skeleton minus its musculature, the pieces of the camera lie on the surface of the picture as if collapsed in a pile. The image, which reveals the complexity of the mechanism and the surprising delicacy of its parts, also serves as an apt metaphor for the dismantled hierarchies of the digital age.

A suggestion of just how the digital realm is reorienting our relationship to time and space is the most compelling aspect of this show. Conceptually, the picture plane offers a view that is downward and horizontal. Except that it doesn’t, because the works are mounted vertically on the wall. It is a confusion that profoundly disorients cultural assumptions about what constitutes the space of looking. Whereas the picture plane used to open up onto the Quattro Centro, viewers now contemplate a terrifying vista of emptiness.

All works in the exhibition fall within the genre of the still life, the artist using cheap props like plastic fruit or the brightly colored lures used in fly-fishing. In each work’s title he specifies the paltry cost of the props, helping to emphasize an enduring aspect of the memento mori’s message that human’s are vain, time is empty and life is futile.

by Rosemary Heather

This text originally appeared in Flash Art, Nov/Dec 2006.

Evan Lee is represented by the Monte Clark Gallery

A student of the film, Horton has been engaged in an ongoing process of reconstructing it. In each of the works 200 diptychs, a still from the movie is mirrored by its hand fabricated facsimile. For each one, the artist begins by making compositions that break down the volumes of light and shadow in the Kubrick original. Working with objects close to hand in his apartment, the wit of the enterprise comes with his choices of substitutions: a fork for an airplane fuselage, a tight close-up on a scoop of vanilla ice cream for clouds, a plastic bag for the sky. The net effect splits the difference between Horton’s artistic ingenuity and his humbling of the British filmmaker’s cinematic artistry into a mere series of constructions. Pursuing this line of enquiry helps to place Horton’s work within a larger trend that sees artists using the hand-made as a way to puncture the spell of illusionism. Considering that much of contemporary life is undergoing a process of fusion with the virtual world, it is a reassuring development, one that proves art’s relevance as a corrective to tendencies in the wider culture.

By Rosemary Heather

This text originally appeared in Flash Art, October 2007

Kristan Horton is represented by Jessica Bradely Art+Projects, Toronto.

Like a fifth column, Framer has always lurked in the shadows of his own practice. His aim is, however, not to destroy but merely express ambivalence. One constant in his work is the use of video to make literal the idea that the exhibition space is the site of something that’s already happened. So the artist has used an art gallery to show a video of himself skateboarding there after hours, or another to show video documentation of himself making tin foil sculptures with his feet. For his Jeffries’ show, the installation evolved, the viewer encountering traces of the artist’s nocturnal actions: His drawings pinned to the wall; the fuselage covered with scraps of colored fabric; the artist seen on a monitor wearing a child’s skeleton outfit and climbing a ladder. Creating layers of time and space in the gallery, Farmer reflects on the role of the artist as presence and actor: and of conceptualism as a practice that is, of necessity, always reanimated.

By Rosemary Heather

This text originally appeared in Flash Art, January/February 2007

Geoffrey Farmer is represented by the Catriona Jeffreis Gallery, Vancouver

The romance of the truck stop may sound like worn-out material for an artist to draw on. The idea would seem to evoke a familiar landscape ¬- one that is, let’s face it, from the last century. In Air Cushioned Ride (2007) the Berlin-based Albanian artist Sala makes the territory his own. A car-mounted camera slowly circles a row of 18-wheel vehicles, a scene that is set against the dazzling blue big sky of some nameless open country. Along for the ride is a soundtrack that alternates between two songs, on a country music and a classical music station, respectively. For the show’s opening, Sala had this composite tune arranged for live performance. Producing a full-bodied replication of the work’s soundtrack was a combined and rather large group of authentic-looking country/western and classical musicians. It was a novel accomplishment and something of a technical feat. What it added to the piece as a whole is less certain. The artfulness of the adaptation is its weak point proving that, in conceptual practice at least, antipathy to technique remains steadfast. Sala’s film, on the other hand, is entirely artless and so that much more successful. Initial assumptions about the time and place of the work give way to the realization that the scene you are looking at is not necessarily in the proverbial mid-western US. Country music and long-distance trucking are Americanisms that are at this point merely part of the general condition of things in the West. It is this fusion of old world and new that the artist neatly encapsulates on his soundtrack. By articulating an idea about the universality of placelessness, Sala achieves an absolute contemporaneity. Bypassing the easy clichés of pop culture, he carves out a concrete piece of the present.

By Rosemary Heather

This text originally appeared in Flash Art, July-September Issue, 2007

Anri Sala is represented by Johnen Galerie, Berlin

RH

You used to do work on paper and now what do you do?

SB I’m still doing work on paper but I’m doing a lot of different things, a lot of photograms, photo collages, painting and drawings still, installation pieces or room pieces – pieces that are specifically adapted to exhibition space.

RH And what’s the thing that ties it all together?

SB I guess the content that I’m working with is similar in different works that I make. But then I always come to a different sensibility in making it. So something might lend itself to becoming a photogram or something might become a silk painting. Or something might become an architectural sort of project but this comes usually within the process or even before the process when I’m thinking about what I want to make. I want to work with this picture I found in the flea market. Or I want to work with the The Golden Notebook. Or I want to work with Martha Graham. And these things are usually parts of bigger bodies of work…I usually have two or three kind of bodies of work that are close together in content and then I try to keep free with the technical aspects of making it. Because often I make things more than once and the way I make it has to be very specific for it to function. I guess it’s kind of about form and function too.

RH You know what you want, you know how to get it and then you just…

SB Yeah, you just kind of pick up things along the way. Because the way something is made or using different mediums I think is just a sensibility that comes with trying to be really clear about saying something in a unclear way that doesn’t relate directly to the content. So my process is really necessary to show itself as content. And this is something I think that merges together with the original starting point of the idea that I have.

RH Why do you want to say something clearly in an unclear way?

SB I mean to say something in a non-narrative way, not one-to-one with the original, the original content or form rather, because I often use a photo or make reference to something that already exists. And so I don’t want to just simply appropriate – it just doesn’t work for me to work with one-to-one appropriation.

RH This is something I noticed, for instance, in Six or Seven Wolves (2005-2006), that the wolves are depicted in an indistinct way.

SB Yeah.

RH And then also there’s only five of them…

SB Yes. This is a good example. I can take you through the process this way. This was in the Case Studies…Freud’s case study, “the Wolfman” where the patient’s Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder was traced back to this dream that he had explained in one of his sessions. He had this dream when he was about three or four, he said. And he looked out his window and he saw the six or seven wolves and they looked like white huskies. They looked like they were white wolves with (sheepdog) tails, they had really bushy tails and they were all staring at him. And it was completely unheimlich, uncanny. And he did a drawing in one of his sessions with Freud and he only drew…there’s five wolves I think in the photographs. He only drew five wolves in his drawing but he said there were six or seven wolves. So because of this Freud went through I think four pages of his own interpretation of why these two wolves could have been missing. He thought that the two wolves maybe stood for his mother because he had seen his mother having sex with his father’s wife in the doggy style position. And another example was, there was a fairy tale in Europe called the Wolf and the Seven Little Kids. It’s kind of like Little Red Riding Hood but with more characters. And I think there’s something about all of the kids getting eaten except for one who hides in the clock case-Freud also connects this fairy tale because the wolf has the baker whiten his paws to trick the baby goats.

RH Four pages of Freud’s analysis specifically about the fact that those two wolves were missing.

SB So what I wanted to do was to try and make my photogram as similar compositionally as I could to this drawing from Pankejeff, I think his name was, the patient. So I went through like literally hundreds of images of walnut trees without leaves to try and find one that worked like the one in the book, in the drawing that I had seen. And one of the reasons that the wolves were kind of similar is because I drew them myself. And when I was younger I drew, I think this is one of those Canada things, like I drew animals, wolves, wild animals quite a lot. So it’s just natural to draw wild animals…I researched Arctic wolves; I found them in the right positions and added these sheepdog tails. And then in the whole lighting process with the photogram you don’t really have that much control over what it’s going to look like because I’m using cheap computer prints on A3 transparent paper in this work in particular. And so how the wolves and the tree come together in the end is kind of out of my control to see how the borders will look or what will happen. I guess what I am what I’m trying to do is to clearly determine a certain kind of psychological space. Or a certain kind of attitude that comes from my re-assessment of a lot of different material values and a lot of different stores of meaning that comes from working through what I see.

RH This is quite clear, that you create this psychological space and the image of wolves looking at you seems very powerful. And it also has this real world reference to this actual psychoanalytic case study, a famous case study. This creates a division between the way the wolves are depicted and the idea of what’s depicted, and what’s beyond the surface of the work. This connects to what you were saying before about how the work embodies a relationship to the content.

SB Yes.

RH You said in a previous conversation that your goal was to create ornament as content?

SB Yes, something that John Dewey said is that ornament is usually dissociated from its sourced content. So if you have for example a Heriz carpet. I have a Heriz carpet at home.

RH What is that?

SB It’s a region in Persia. I stare at it all the time. The emblems and the ornaments in the Heriz carpet have been divorced for their original tribal and political associations. So two hundred years ago, three hundred years ago, the ornaments in these carpets served as a kind of admission to cultural meaning for the people who lived in this town who made these carpets. And then these carpets became very valued in the West. They became really popular because they’re quite tough and they’re also very harmonious, very geometric. And so they started to change the ornament based on the wishes of the Western consumer. So now a Heriz doesn’t have the same ornamental values, the meaning of the ornament is not there like it was before. It’s made for Western people now (and) the ornament isn’t associated with the meaning of the town itself. And this is something that I find interesting because when you’re using ornament today you can’t really take the face value of what it means.

…

SB In my Six or Seven Wolves drawings series, I was using ornament as an atmospheric quality. Its less of decorative thing. But then as I came further along I realized how ornament can kind of, can function as a base in its own right. You can take these…the original context it gets suspended and it becomes something else. It indicates something different than you would originally expect, something that’s not decorative. The purpose becomes depth in itself. Normally when you see ornament, you think of it as something that covers the surface, and it makes things pleasing to a viewer because you have a scientific relationship to geometric configurations that makes you feel good when you look at them. That’s why ornament can be very dangerous because it’s a cheap draw-in for the viewer. You don’t want to kill with kindness.

RH What do you mean dangerous?

SB If you work with ornament and it’s not specific it can just be something that, it can just be a pleasing element. It can be a darling, you know it can be something that you…

RH Which is not what you’re trying to do.

SB No. But I see it in contrast to using something that draws the viewer in. I think the draw, the ornament…I see it as its own entity. These days for example if you want to try and use Cartesian perspective to show deep space it’s really like a sleeping pill because you can’t compete with Hollywood. You can’t compete with all of these special effects things that have really simplified and flattened deep space. And so what I would like to do or what I try to do in some of my work, or a lot of my work, is to look deeply at a surface and to see what the surface resolves in a deeper way.

RH This segue ways nicely to the floor work Schraegraum (2005) This is a Photoshop work that actually translates Photoshop perspective into real thing on the floor?

SB Yeah it was more about the idea of living with a material on a regular basis. So we have a lot of surfaces that we take for granted.

RH Yes.

SB Or surfaces that are just in our space. So something like a laminate, it’s kind of a paradox that we accept it as a real spatial existence.

RH Right.

SB And also I think a lot of artistic developments take an angle on, on certain materials or certain kind of technology when it hasn’t really been pushed to its limit. We don’t really know how we can translate an idea like laminate into a different space. And it’s also dealing with more of like a suburban sensibility as opposed pop culture. Some kind of breakdown of values that are just generally taken for granted in a visual space.

RH I don’t think it’s a very common concern at the moment of dealing with conceptual issues in two-dimensional representation? It seems to me what you’re doing is kind of unique.

SB Yeah it’s not; it’s not a common practise definitely.

RH No, it’s not like the big collective project to develop cubism.

SB Yeah that’s true.

RH Maybe you can give some more examples of the idea of surface and space. What about Origin/Inversion (2005) It’s a wall drawing and it’s drawings of carpets?

SB Yeah, it’s both. One of the carpets is from a painting by Jan van Eyck and the other one is from a painting from Hans Memling. They’re both from paintings from the fifteenth century. Perspective started to get configured back into painting at this time. But these are paintings from the Northern Renaissance. And instead of this Cartesian Italian approach where it’s almost like a stage set because the perspective is so perfectly crafted, (where a narrative is really balanced into the composition), what you have with the artists who were working in the North, like Jan van Eyck especially and Hans Memling is a very meticulous rendering of surface. So the end effect is more a kind of atmospheric sense of content, the content is less about the narrative that’s happening and more about the resonance of the different materials that are depicted. And this is also the origin that I have of the work, Schrägraum (2005), the laminate (floor). Schrägraum is a term from Panofsky. He’s talking about how the perspective of the Northern Renaissance painters is often crooked. Because they didn’t have the linear perspective perfectly executed. What comes out of that is a different reading of the space. He wrote about its’ psychological quality, which I find interesting, too). So this (my point of origin in) working with these kinds of surface materials to see how they resonate into a new reading of space.

RH Well I mean, why put the drawing of the carpet on the wall?

SB I wanted to make it architectural, (and bodily)

RH It’s in the corner.

SB I designed it on the computer to go in the corner. In the original paintings, the carpets were on the ground and then the perspective goes up the floor with the carpet. Each carpet serves as the starting point of the painting‘s perspective. And what I did was I put them together, because they both have a slightly different perspective, and inverted them on the wall.

RH Then there’s the pedestal.

SB This is a piece of laminate that I also wanted to ground it with another aspect of fake material that would add to this atmospheric quality. So I, I built (the) sculpture to rest on the floor to give it more resonance.

RH It’s like an apron.

SB Oh yeah.

RH And then there’s this coffee stain here. What is it?

SB That’s a wheel.

RH Oh, okay.

SB This is the Wheel of St. Catherine.

RH Uh, huh.

SB Because this is from the Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine by Memling, And it’s St. Catherine’s wheel. These carpets are all from the Ottoman time. These paintings also show the emergence of capitalism at this time. The fact that people started to trade with the Orient. And this is one of the first examples of…

RH Merchant capitalism.

SB It’s a good example of ornamental qualities being taken out of their context and used in another artistic platform.

RH The ornament from the carpet being used in the painting.

SB Yeah, then it becomes about the wealth of the church and doesn’t have the tribal connotations anymore.

RH I was interested to hear you speak about your process being dissociative. So maybe you could talk more about that?

SB Well, the idea of dissociation in its basic terms is the idea of splitting off. So it’s the idea of you losing contact with the present world and going somewhere else but in a non-hallucinatory way. It’s more about splitting from yourself. I connect this to drawing and the process of making work. What I find interesting is to use a sometimes very dissociative process of making work, which has to do with the repetition of making. The idea of making ornament is also very dissociative. If you look at Outsider Art – or art from The Prinzhorn Collection, for example – a lot of it is extremely dissociative.

RH What’s The Prinzhorn Collection??

SB It’s in Heidelberg. He was a psychiatrist who started collecting his patient’s work and naming it “art” in its own right. I think it was in the 1920’s. (I am off in the original, it was from 1919-1922 that he really started collecting) There’s a permanent exhibition in Heidelberg, you can go and see it. And then Dubuffet and Art Brut took up these ideas. With this kind of art you don’t have the division between the self and the paper. The ego of the person goes directly onto the work itself. There’s also some sort of psychic connection to what you’re making. But when I think of dissociation it’s this idea of, especially when I’m using something like ornament, I’ll start with a very analytical perspective of something that I want to make; or something that I want to say. Then in the process of making it something else comes up and often this has to do more with continuing the process itself than staying with the narrative content. And it starts to layer itself and its something that you can’t really edit that carefully. You can’t start from the beginning and say oh, the work is going to be like that or I think the work should look like that because it never works out that way.

RH So you use narrative references, like ornament, to create content about the process of making art.

I think that relates to the fact that you it does create a psychological space in your work, like in Six or Seven Wolves, for instance. So, maybe we can talk a little bit more about that?

SB Yeah.

RH It’s kind of a fraught psychological space.

SB I guess you just never want to make it easy for the viewer.

RH Why not?

SB This is something that you can connect ornament to. The idea that it’s a comfort zone. It’s like icing or it can be like mashed potatoes in a work. And if you have too much of that it becomes less about creating the work in a smart way or understanding more complicated aspects of the work. It doesn’t go deep into anywhere, not even the surface. It just kind of satiates the viewer. And it has to do with being comfortable within your own process and comfortable within your studio process, and what you’re using, the materials you’re using. This mannerism that’s created, it’s dangerous. It’s the dangerous thing about ornament and it’s something that you have to avoid.

RH Have you read Adolf Loos’ Ornament and Crime?

SB Yeah, it’s great. But Loos was really hard on ornament. He compared ornament to Maori facial tattoos (I don’t want to quote Loos directly with “savages”), that they have ornament even on their face shows how lower they are the Darwinian scale. And he (wrote) about prisoners, that they tattoo and decorate their bodies and how this is another example of how low ornament is. I thought it was brutal when I first read it. But then the first time I went to Vienna I could see his point of view because everything is so ornate and decadent there. And then you go into this café that he designed, the Museum Café and it’s just like a breath of fresh air. And you see these Art Nouveau buildings everywhere and just coating after sugar coating of ornament. So I think that for ornament to function is has to be aware of this aspect of cancelling itself out. It has to know its limitations.

RH I read a book by Rebecca West, a book of essays. In one of them about the Nuremburg Trials, she said something about how she could see in German architecture the non-restrained detailing was indicative of the decay of that civilization.

SB But this is true in every art movement you have a point where the scales start to tip and the work becomes comfortable with itself and it becomes, it stops functioning because it knows what it’s doing too well. So that’s why I think ornament is dangerous because it has to be used in a new way. You have to look at it in a way that looks at its intrinsic value- not just its original intrinsic value, but the terms of how it functions in a space today.

RH Well bearing in mind this idea that it’s dangerous, this is one of the main tendencies in your work ornamentation, pattern, detail…And it occurs to me that this dissidence is built into it, there’s always a disruption in the pattern field…

SB This is this wall-paper work Liquid Pizzeria (2004) where I had an architect design this disruption in this pattern from cheap pizzeria wallpaper that you find in pizzerias in Germany. I wanted to use this idea of futurism, of depicting motion and space but using the wallpaper as the background for this motion. So I had an architect design this swirl for the wallpaper but then I hand collaged it because I wanted to, to me if I had just printed it out on the computer this work would have been too boring. So when you see it, it has these hand collaged little bits in it so it really slows down the reading of the work. Which is really mucked up.

RH But I mean this swirl, it’s a brick pattern, no?

SB Yeah.

RH And when you asked this architect to do it, what did you ask him to do?

SB I wanted to have some photo disruption in the space so she just showed me different designs and ideas and we sat through a session of looking at different things that could happen and then I decided on this one.

RH Can you talk about the floor?

SB Yeah, I just, this is an idea; this is another very dissociative idea. And I thought this work was really formal.

RH What’s it called?

SB It’s called, Partially Renovated Floor (2004) And it’s funny, because I thought this work was very, very clean and formal and then a conceptual artist that I met told me that it is more of a fetish work.

RH Oh, yeah that’s interesting.

SB Which is true.

RH Yeah, yeah.

SB And I think this work is highly dissociative because it came from being in one of the studios I worked in when I was at the Staedelschule in Frankfurt and staring at the floor for a year. It had originally been a studio from the Hermann Nitsche class so there was a lot of shit on that floor.

RH And, basically, you scraped it away?

SB I just renovated a part of it. But then you see the difference, and one of the reasons I did it was that the floors are very, very expensive hardwood floors, they picked the best kind of hard wood floor for the studios.

RH Is it parquet?

SB Parquet for the studio spaces and these studio spaces were supposed to become painting studios and the architect knew that but he still wanted this floor.

RH Right.

SB And then after twenty years it was covered, you could just barely see some of the lines of what had been underneath.

RH So what is this covered in?

SB You can see close up, like, just paint and dirt.

RH It’s just dirt.

SB Well mostly paint. I think. Like it’s mostly just oil paint that gets squished in different layers over the years. And then worn in dirt that gets stuck to the paint and also some other stuff like beer and…

SB But then one of the things that I found interesting… other content comes up after you sand through. I was showing a different part of the Staedelschule from a time when it was so rich. The school was so rich in the 80’s that they would send full classes of students off to China, all expenses paid for two weeks. And they had the money to say, oh, we’ll use the best parquet for the painting studios, no problem. So when you make these sorts of gestures,( like sanding and polishing the floor) other information gets implicated (into) the original intention.

…

This interview originally appeared in C Magazine, Issue 92.

Shannon Bool is represented by Galerie Kadel Willborn.

Melanie O’Brian, Director/Curator of Artspeak in Vancouver for the past six years, recently moved to Toronto to take up the post of Curator & Head of Programs at The Power Plant. With this appointment, O’Brian makes the shift from what’s known in Canada as the artist-run sector to one of the country’s major venues. We spoke over email in March, 2011.

RH: Your professional career up to now has been firmly rooted in Vancouver. How do you think this experience will translate to Toronto? Do you expect to shift your priorities, or will you continue with the type of programming you developed at Artspeak?

MO: My goal is to maintain a strong foundation in the local while intersecting with international practices and dialogues. My programming interests regarding site will undoubtedly shift at The Power Plant. At Artspeak I addressed the institution’s mandate to reflect a dialogue between language and contemporary visual art and I also extended the program outside of the limited confines of the gallery. Through the OFFSITE program (2008-2010), I took artists’ projects into various ‘public’ situations using the street, parks, print, large-scale advertising, building sites, the postal system, etc. While I certainly maintain a desire to do offsite projects in Toronto and address contextual specificities, the institutional spaces at The Power Plant will allow me to initiate projects that would never have been possible at Artspeak.

RH: Speaking about OFFSITE, why do you think art institutions feel the need to develop audiences beyond what you refer to as the “confines” of the gallery? Is this tendency artwork-driven or institutionally-led?

MO: Artists are engaging strategies that re-activate wide cultural, political, and economic discussions within the process of art production and its reception. Institutions are encouraging this activity, often arguing that the audience for contemporary art is wider than ever before. But only a select audience overtly sustains contemporary art’s dialogues. Contemporary art is intersecting with audiences on multiple levels from the gallery to the street, from the blockbuster to the festival, from the biennial to the incidental. Perhaps the spectacularization of contemporary art’s presentation is a point for discussion?

RH: Toronto has a wildly successful Nuit Blanche event, presenting public art works across the city for one night. It attracts an estimated audience of one million people. The number one criticism of the event is that it tends to feature spectacular artworks. This could be seen as pandering to the crowd, or it could simply reflect the changing nature of art. Any thoughts?

MO: These types of events are increasingly common, whether autonomous or embedded in the Olympics. They do not necessarily reflect the changing nature of art, but rather the changing nature of the art system.. Art fairs, biennials, and other large scale spectacles provide a point of comparison. They are formats that often request, if not demand, art that competes with or withstands the spectacle. I might add that in what could be touted as a post-relational aesthetics, post-participatory moment, artists and artworks must not just engage with the art system, but intervene in it and question it productively.

Interview by Rosemary Heather

This text originally appeared in the May/June 2011 issue of Flash Art.

Melanie OBrian is the Editor of Vancouver Art and Economies, an anthology of writing about the Vancouver art scene, which can be purchased here.

Ransacking the past, while denying any knowledge of it, has always kind of been the program for artists. Suppression of your antecedents is a good way to create a neat little package from your own historical moment. This was also true of pushed-to-the-sidelines non-Western traditions in art. A recent show of Picasso’s work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, for instance, gave viewers an eye-opening if perhaps not entirely intentional look at adjoining rooms full of his African and Oceanic source materials.

Not that it matters much at this point. Our own historical moment has a rather more pressing need to seek out continuities with the past and other artistic traditions. Motivated by this impulse, Scream helps to dismantle another long-standing partition, between Inuit art and contemporary practice. Scream is a companion exhibition to last year’s Noise Ghost, which featured Toronto’s Shary Boyle and Cape Dorset artist Shuvinai Ashoona, and takes a similar approach, pairing Ed Pien with Samonie Toonoo, artists who reside in the same two respective locations. Resonances in their work begin with an interest in the figure; it is a common denominator that points to a primordial intelligence always at work in art. Curator Nancy Campbell makes this reading explicit by titling the exhibition after the famous painting by Edward Munch. She connects three points on a map rendered in space and time. As the show makes apparent, once these connections are drawn, certain assumptions start to become undone.

The expressive potential of the figure is powerfully put to use in Toonoo and Pien’s work. Toonoo presents stone carvings, embellished with detailing – of a fur fringe on a hood or a face, sometimes a skull, carved in bone. Each carving tells a story, often tragic. Pien’s drawings are created through a process he calls monoprinting. Taking quickly drawn sketches in coloured ink, he creates overlapping compositions with the wet ink applied to fresh paper, often placed on top of other drawings, or cut out and collaged together. Combined into large densely layered composite pictures, the effect is mesmerizing.

By strictly adhering to the elements of line and color, but at the expense of volume, Pien creates drawings that look stencil-like, and further evoke the ancient art of Chinese brush drawing. Pien is an Asian-Canadian who immigrated to Canada from Taiwan at the age of 11. While reminiscent of Chinese art traditions, the artist reports he developed the monoprinting process in the course of his art practice. The technique is entirely his own. Born into a family of artists, Toonoo has deep roots in the artmaking traditions of his people. He adds embellishments to traditional-looking stone carvings, such as a figure brandishing a wooden hockey stick, or cross hung around the neck of a hooded figure, to clearly place his work in the contemporary world. Detailing allows Toonoo to align obdurate stone and Inuit carving techniques with drawing, and drawing’s aptitude for editorial commentary.

Loss of a need for boundaries, between not only artmaking epochs but also artmaking traditions, suggests we have arrived at a historical moment free from pastiche. Instead, artists are seeking out the terms for a deeper kind of renewal. Once again art proves its relevance as a prognosticator of what is to come: a loss of dominance for the West in a Globalized world.

By Rosemary Heather

This text originally appeared in Hunter and Cook, Issue 07

Scream was presented by the Justine M Barnicke Gallery, University of Toronto from June 10 – August 21st, 2010

Ed Pien is represented by Pierre-Francois Ouellette Art Contemporain, Montreal

Samonie Toonoo is represented by Feheley Fine Arts