Among the legion of painters devoted to figuration, Michael Lewis maps out a distinct place. In his large-scale works, the dimensions of painting become the constricted space of everyday urban existence: the hotel hallways, office buildings and banquet halls. Windowless rooms contain faceless people, all of them suffering from some nameless torpor. Primarily a painter of interior spaces, Lewis frequently includes potted plants in his pictures to provide a (somewhat cynical) reminder of natural life. When Lewis does paint the outside world, his landscapes look suitably alien.

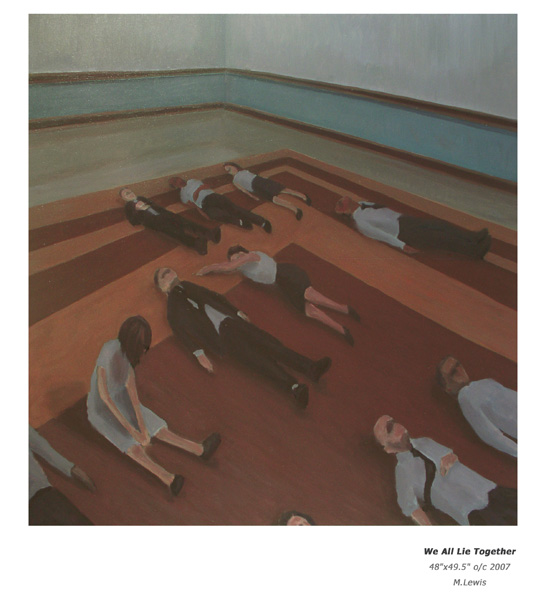

Sometimes the torpor in Lewis’s work is depicted. In ‘We All Lie Together’ (2007), a group of people lie on the floor. More often, torpor is just an ambience pervading the work. The artist uses a tepid palette of blue and green to serve psychological ends. There is no air in these rooms. Often the paintings are tinged with an undercoat of red, giving them an eerie vitality. The subtle reddish glow suggests a painterly corollary for disquiet.

Lewis used to be a bike courier and he told me this may be the reason why the mise en scene of his imagination always ends up looking like the lobby of an office building. In his paintings, people are busy but it’s hard to say what exactly they are doing. Allegories of office job deadness, bomb shelter anomie or consumer culture conformity all spring to mind.

More to the point perhaps is the claim Lewis makes in his paintings that his medium conveys meaning. His work recalls a quote of Rene Magritte, who described painting as “the art of putting colors side by side in such a way that their real aspect is effaced.”1 In Magritte’s view, a successful painting achieved just that, a kind of poetic coherence, one that “dispenses with any symbolic significance.” Lewis’s work achieves this coherence. His paintings give an impression of profundity; numerous potential readings could result. Our willingness to invest in the work’s reality is connected to the artist’s motives when making it. In the end, however, all readings hit up against the limit of what Lewis’ works actually articulate: the artist’s skill at painting.

1. Frasnay, Daniel. The Artist’s World. “Magritte.” New York: The Viking Press, 1969. pp. 99-107

By Rosemary Heather

This text originally appeared in Hunter and Cook, Issue 09

Michael Lewis is represented by the Meredith Keith Gallery.

Michael Lewis’ website is here.