Recent history tells us that the experience cinema offers is excessive. The belief that it is necessary to go to a theatre to see a film is already a thing of the past. Cinema was an industrial innovation. Based on an economy of scale, the commercial premise of the business is that each member of its audience possesses a quotient of popular taste that the industry can replicate and nurture in each new film it devises. The basic assumption of the format used to be that this mass psyche could be unlocked by a film’s presentation in a setting of anonymous camaraderie; in other words, the belief was that people would want to watch movies together in the dark. But these conditions now appear to be unnecessary, or so the popularity of sub-par viewing formats like YouTube and iPod movies would seem to suggest.

In her exhibition, The Castle and other works, Annie MacDonell looks at this history from the perspective of today, a moment when cinema is being eclipsed by newer formats of entertainment. Giving depth to this view, her show looks beyond film to its origins in Vaudeville. Consisting of remnants from this past, MacDonnell’s exhibition offers insights into the wider cultural demands embodied by these continuities, suggesting that the need for diversion, for a parallel realm of spectral distraction, exceeds any of the formats invented for its possibility. It is this need’s ability to conjure up the means of its realization, if not an explanation of its source that MacDonnell’s show evokes..

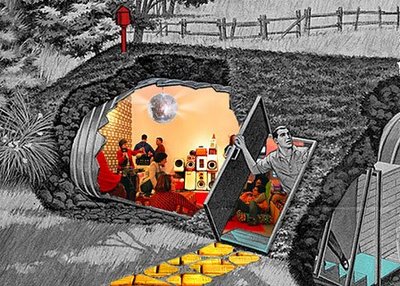

In The Castle (2006) a sculpture of a chandelier sits on the floor of the gallery as if it had recently crashed there, or, in more grandiose terms, had somehow fallen to earth. A non-functioning replica, the chandelier illuminates nothing except protocols of ornamentation to which we are no longer accustomed. Ornamentation was, however, once thought of as an important aspect of the movie experience; film theatres were after all referred to as “palaces.” This connects the chandelier to MacDonnell’s Untitled Vaudeville Models (2006), which MacDonnell built in collaboration with Rob Shostak. They consist of three scale models of Vaudeville theatres in Toronto, all of which date from the turn of the 20th century. That Vaudeville theatres tended to be turned into cinemas, which are themselves now on the wane, points to the larger theme of the show. The condition of spectatorship was once located in spaces built specifically for the purpose, but it is less and less dependent on physical circumstance.

In The Castle (2006) a portly man in a video projection is seen falling through space. He stumbles down the stairs and then the action is magically reversed. The cycle repeats. By looping the video, the artist arrives at a kind of perpetual slapstick. The artist abstracts the base humor of Vaudeville, its broad physical comedy, to evoke the idea of entertainment itself. The man’s appearance reinforces this impression. Middle-aged and out of shape, his mustachioed visage evokes an archetype: not a leading man or captain of industry but rather an avuncular figure of fun, like Stan Laurel or Fatty Arbuckle, familiar from the early days of the entertainment industry. A likely inhabitant of both smoking jacket and smoking lounges, he evokes the pathos of manhood past its prime, still the beneficiary of male privilege but some years beyond the ability to make meaningful use of its powers.

Art exhibitions tend to consist of discrete objects ¬– whether of the thing itself or of some form of its representation – presented in meaningful combination. The custom is for exhibitions to occur in a definite space, or make reference to that space, which is known as “the context.” The placement into this context of any artwork that takes the form of a real entity (as opposed to an abstraction of such) should be understood as having been removed from the circulation of utilitarian items for a reason. In the same way that the art gallery is more than just a space for the exhibition of objects, the artwork is both a thing in itself and what it represents. The artwork in itself refers to every possible realization of the idea of art, especially those that have already occurred; and the entity it represents refers to the wider world of meaning from which it derives.

Although susceptible to many definitions, the artwork’s ability to incorporate within itself multiple dimensions of significance means that it always in some sense functions as a synechdoche: the work of art or the art installation is always the part standing for the whole. Writing about literature, the critic Terry Eagleton discusses how the reader of a literary work “unconsciously supplies information which is needed to make sense of it.” “All literature is understated” Eagleton notes, “even at its most luridly melodramatic.” The same could be said for art. MacDonell’s show makes use of the synechdochic power of the artwork, and also makes an exhibition that is about this synechdochic power. The artist doubles the synechdochic resonances of her show in the sense that it is about just how little it is that we need from the real world in order for us to imaginatively exist in the spectral realm, and for that realm to fulfill the wish that we could exist there.

If early cinema took the basic elements of Vaudeville as its starting point, this is in part because film’s illusionistic qualities were so well suited to the art form’s vulgar comedy of physical mishap. The idea that someone can fall without getting hurt, the basic fact that the moving image finds its origins in release from the consequences of the physical, suggests a number of things: that entertainment is strangely predicated on the misfortune of others, and, more broadly, that the cinema fulfils a wish that the physical world could be more benign than it is. This connects MacDonell’s fallen chandelier and tumbling man to another work in the show, Sunset Signature Lounge (2006). Housed inside a small freestanding cabinet with room enough for only one viewer at a time, the work features a slide-projected image of a sunset as seen from the 96th floor of the Chicago’s John Hancock tower. One of the tallest buildings in the U.S., a centerpiece in a city famed for its architecture, the building’s Signature Lounge provides Chicago’s citizens with a cocktail hour ritual. The image was shot at twilight in the lounge, a bar that features floor-to-ceiling plate glass windows. Looking at the phosphorescent and warm transitional hues of the sun as it sinks below the horizon offers the best accentuation of this, as it fuses the experience of the sunset with its image. It is, as MacDonell comments, “an intensely American experience, ” the impact of which is such that the lounge patrons often break into applause upon viewing the sun’s final curtain, so to speak. It is as if each floor of the John Hancock tower was only the premise for the next one, and this continues upwards until the building was tall enough to create the perfect platform for the viewing of each day’s end., The floor-to-ceiling plate glass windows were installed to more perfectly frame the experience, transforming it all into a two-dimensional picture of itself. Finding that cinematic desire lurks even in aspects of the built environment, the artist points out just how eager we are as a culture to step off into the virtual.

MacDonell designed the installation so that the sound of applause, which is preceded by a soundtrack of ambient noise and soft chatter, subtly permeates the exhibition as a whole. If not actually creating an immersive experience for the viewer, the sound in the exhibition points to the aural aspect of spectacle; its aim is to be thoroughly persuasive. To undercut this, and to indicate that what she is offering is not spectacle per se but the means for a critical reflection on its powers, the artist positions the slide projector outside the cabinet, which itself is left unfinished, and leaves the work’s speakers, amplifiers, and their connecting cables and electrical wires exposed on its top.

The artist’s suggestion about how easily natural phenomena are incorporated into an overall cultural preference for spectacle connects to the show’s wider idea that our culture is constantly looking for the means to make our reality into something that is more free of consequences and more under our control than it is or ever could be. This idea applies especially to how we participate in spectacle today, which because of the Internet and portable digital devices extends far beyond the physical space of the movie theatre. This suggests that it’s not the cinema that is excessive but only the cultural desire for its pleasures. If this fact is more apparent than ever, being able to recognize it still tell us little about what it means. Full participants in this virtual onslaught, cinema and other forms of spectacle have only a weak ability to reflect on the phenomenon. Artworks, on the other hand, exist to be reflective, and in the process can reveal an entirely new dimension to, for instance, the fun Vaudeville finds in misfortune.

Rosemary Heather 10.15.06

This text was commissioned by Gallery TPW to accompany Annie MacDonell: The Castle and Other Works, October 26-November 26, 2006.

More information about Annie MacDonell can be found here, here and here.