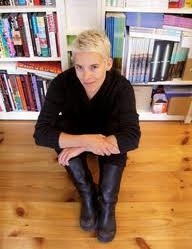

When forgotten, pop stars become like wallpaper in our daily lives. Once they become ensconced as icons, they take on an ulterior function. Probably only students listen to Bob Marley these days, but this doesn’t stop me from singing on of his songs, involuntarily, when walking down the street. This is one of the subjects of Candice Breitz’s work. By recording a popular song as sung by its multitude of fans, or taking the overly familiar images of media stars and breaking them down into their constituent parts, Breitz makes evident the unconscious roles these icons play in our lives. If the idea of ‘Clint Eastwood’ has become as natural to us as a tree, Breitz works to make sure he comes to seem unnatural to us again, helping us to decode our world and understand it a little better. In Factum (2009), commissioned for her solo exhibition at the Power Plant in Toronto, she worked with sets of twins to literally construct a composite portrait of their public selves. Splitting the one into two–two people on two screens who look all but identical–serves as a nice metaphor for her practice as a whole, which reconfigures the mediated world into a self-reflective entity. I spoke with Candice in September 2009 when she was in Toronto for the opening of the Factum exhibition.

You’re working with not necessarily the newest stars but the most established. Figures like Bob Marley, Meryl Streep are so ubiquitous they’re almost beyond conscious attention. Even when I was preparing for this interview, I got Buffalo Soldier stuck in my head…

Candice: It happens to the best of us! There’s an excellent German word for this phenomenon… a song that gets annoyingly stuck in one’s head is called an Ohrwurm or Earworm.

This goes the heart of what you’re doing. You could have chosen Colin Firth or Brad Pitt, so I’m just wondering what it is about those stars in particular that interest you? Is it because you’re a fan?

Well, I’m interested in the kind of patina that celebrity acquires with a little bit of distance. And I think that—with very rare exception—I haven’t really been interested in addressing things that are happening now, things that are too

contemporary, because I think it can be hard to understand things when you’re standing right in front of them. In a sense, I’m much more interested in material which has the potential to tell us something about who we were, who we have been in relation to who we are now, than in material that claims to be able to tell us who we are right now. So much of what is happening right now won’t remain significant in the long run; it won’t have that Buffalo Soldier quality. From the vantage point of now, it’s hard to tell which cultural moments will be collectively internalised and

become part of our shared memory and our ongoing cultural being: proximity can be blinding.

You could say that I’m interested in treating the footage that I recycle almost archaeologically. I made an installation in 2002 that I titled Diorama, using short clips from the soap opera Dallas as my raw material. That was the first time it

occurred to me that the television screen is somewhat like a vitrine – you know, you visit a museum of natural history and they’ve got stuffed creatures and preserved artefacts displayed in glass boxes, objects that are supposed to open onto a greater understanding of who we’ve been or how we’ve interacted with our natural environment. And so within my installations, I like to think that the television or the plasma display becomes a vitrine of sorts: slightly aged footage can give off a lot of clues as to what our priorities were and are, what values we have aspired to, how current conventions came into being. With a little bit of historical distance, it becomes much easier to translate, to be in dialogue with footage.

And your formal strategies of breaking down the stars’ performances into memes. Do you think that that helps to break down our identification with them… or, as I said, our ability to disregard them, our tendency to treat

these individuals as sort of psychic wallpaper?

We wallow so much in images from the mainstream media, voluntarily or otherwise, that much of this imagery comes to feel almost like a natural landscape, so natural in fact that it can be easy to forget how contrived, how constructed much of this imagery is. To come at it from different angles so that it becomes legible in alternate ways, is a way to acknowledge that the language that is available to us via the mainstream media is a conventionalised vocabulary of gestures and expressions, not to mention constructed forms of behaviour. I’m interested in looking at what terms are privileged by the mainstream, in breaking the vocabulary down: I think of myself more as a minimalist than a pop artist…

Oh that’s interesting…

So sort of breaking it down — as you suggest — into memes. I haven’t thought of my process in those terms, but it makes sense. What are the basic building blocks of mainstream culture? And how do they aggregate to convey who we are? To strip something down—a love song, a blockbuster film, a soap opera—to the basic units that structure it, is to point to its constructedness, to the fact that it has been composed or put together rather than just existing in a natural state…

And that also shows that we do have a kind of intimate relationship with these characters. I think because you reconstruct these images, and present them as an installation, your work sort of acts out this process of the way we internalise these personalities.

It’s certainly not about taking cynical distance… Nor would I want to suggest that I stand outside of the culture that I interrogate or recycle in my work. I’m as prone to this culture as the next person. I think it’s important to avoid dismissing it too readily. Regardless of how self-reflexive and clever we’ve become about picking popular culture apart—understanding its effects and the ways in which subjectivity is inflected through it—it nevertheless has an affect which can’t be swept away, and which I think we have to seriously consider. I think it’s important to try and

understand this affect in its complexity rather than simply characterising it as a negative force and turning a blind eye to it. Why are people so affected by a song or movie that is transparently manipulative or that portrays complex, layered experience in deceptively simplistic terms? People are not stupid. Your average moviegoer understands that they’re being manipulated to some extent, that people don’t appear or behave in reality as they appear or behave on the big screen. And yet the affect remains. I think that’s worth thinking about.

Just to add to that, I was covering the film festival in Toronto and I was at the press office and there was a media scrum around Megan Fox. So I got a little glimpse of her… even though, basically, I don’t know who she is…

I don’t either, but I know the name…

Exactly. And I was still, like, dazzled because she looked so…

…Put together?

Put together. That’s the exact expression that I’d use…

I suppose what my work tries to do is to understand the ‘putting together,’ you know, the consequences of being exposed to so much ‘put-togetherness,’ not only for those individuals who are put together and made visible to us by various marketing forces, but also for those of us who consume the tribe of put-togethers via our cultural habits.

You could say that these globalised stars, like Bob Marley, did the advance work of globalism, because they were global stars before globalism. And yet we’re moving into an era where it could be argued that there’s more diversity and fragmentation of the people who are considered stars, there are lesser stars, the whole B-list to D-list phenomenon brought to us by Reality TV… I’m interested in the fact that your work is also moving in that direction. Your newest project with the twins, Factum (2009), for instance, moves away from stars to real people.

I’m not sure I would agree that working with ‘real people’ is a shift in my practice. Since I started making videos around 1999, I’ve pursued two parallel trajectories. On the one hand, I’ve made a series of artworks using found footage, which tends to address celebrity in its various guises. But I’ve also been interested in the flip side of this phenomenon, not just the people endowed with celebrity and visibility, but also the invisible others who sit and watch the screen, who consume what is on the screen. I’ve made a series of works, starting with a piece called Karaoke in 2000, which are about the reception of popular culture, the fans or consumers that make celebrity a possibility in the first place. My work has tracked both the ‘somebodies’ and the ‘nobodies,’ as Warhol might facetiously put it. In a work like Legend (A Portrait of Bob Marley) (2005), the fans are not telling their stories in a conventional sense, but I think they do tell us a great deal about who they are through their re-performances of the music, in the choices they make about how

they stage their relationship to the music. I think of Legend, and the other projects in which I have worked with communities of fans, as oblique forms of portraiture, attempts to get closer to understanding what it is about listening to music that creates meaning for people, why it is that a particular kind of music gains significance within a particular person’s life.

So working with ordinary people—as I do in Factum—is not really a shift as such. What’s perhaps new about this series, is that it attempts to ask the question, gingerly perhaps, maybe even neurotically, about the extent to which the

biographical experience of ordinary people can survive the overwhelming dominance of celebrity narratives that are at the heart of the culture industry. With genres like biography and portraiture, it’s hard to avoid certain claims for

transparency, certain tropes that imagine a lifetime of experiences as a kind of monolithic trajectory. Factum is my attempt to find a jagged way to look at how a mass of fragments comes together to make up a particular life or, actually, a particular pair of lives. Whether the works are ultimately interesting on those terms, I’m not sure… They’re still very fresh, very recently completed.

And yet you made the decision to dress the twins the same.

I guess that’s the arty part!

It’s beautiful – formally it’s gorgeous. But in terms of what you were saying about biography, there’s a splitting effect there which is interesting in relationship to your older work, it relates maybe to ideas about replication in relation to mass media. Are you maybe familiar with Robert Rauschenberg’s Factum paintings? Do you know them?

Yes, I am.

My series of double portraits of identical twins is named after those paintings. The two paintings are twins of a sort, twins that were separated at birth. One went to live in MoMA in New York; the second is in the collection of MoCA, Los Angeles. That said, I don’t think Rauschenberg was thinking about twins when he mad Factum I and Factum II in 1957. He was probably thinking about the tension between two different ideas about what a work of art is: the work of art as an exteriorized expression of subjectivity, as a product of a creative subject regurgitating its interiority or selfhood, versus the work of art as a thing that is subject, like all other things in the world, to various external forces beyond the

artist’s control. At that moment in time, industrial production—its capacity to produce things en masse through mechanical repetition—was one such force. When Rauschenberg takes a gestural brushstroke and attempts to duplicate it, as he does in his Factum paintings, he predicts everything that was about to happen with pop and minimalism: the work of art was about to be overtly serialised, artists were about to start producing their works industrially in a manner that would echo commodity production. The mythologies so dear to Pollock and the Abstract

Expressionists were about to be obliterated.

Though Rauschenberg may not have been thinking about twins, I think his Factum paintings basically ask questions about how a work of art comes into being… via the nature of the artist… or via the nurturing forces of the larger world as these impact on the artist. My Factum portraits I guess raise similar questions in relation to subject formation. Like Rauschenberg’s paintings, identical twins are at first glance overwhelmingly similar, but the more time you spend with them, the more apparent the differences—subtle and dramatic—become. Despite all the forces of sameness

that press in on us, and there are many, the idiosyncrasy of inner life nevertheless prevails. That of course goes for everybody, not just twins. Delicate as it may be, there is a resistance to homogeneity in the minute decisions that we each make in everyday life, and this is what interests me. Hence the title of the show at The Power Plant in Toronto – Same Same – with its silent ‘…but different.’ I’m interested in the small and quirky ways in which people manage to differentiate themselve under the duress of sameness.

People perform that…

I’m Canadian and it’s often observed that Canadians have a kind of outsider perspective because we’re living next to the behemoth of the US. And I’m just wondering if you feel, as a native of South African, that this gave you a particular perspective on these globalised stars that maybe you wouldn’t have if you had grown-up elsewhere?

In South Africa we only got domestic television in 1976. I wasn’t really born into television, if you know what I mean – television wasn’t there during my early formative years. I clearly remember the day my parents brought a television home for the first time – I think it must have been around 1978; I was about six years old. The single channel that was available was tightly controlled and censored by the state.

A bigger kick than television itself came with the arrival of VHS a few years later: the possibility to selectively view footage, to have some kind of editorial control over what one was watching, to be able to fast forward, rewind, pause. VHS gave my generation the technical tools to break the moving image down in a domestic setting, to start intuitively understanding the constitutive elements of footage and the ways in which it could be manipulated. And once you can break something down, once you start to understand how something is constructed—the very fact that it is constructed rather than existing in some kind of transcendent form—then you can also start thinking about putting it together again in new ways, translating it, rewriting it. Later there would be a number of technical innovations that pushed this process further, but VHS was—for me at least—the first opportunity to think of footage grammatically, syntactically. By shuffling the constitutive elements of any given sequence of images, you can get it to speak different meanings, make it accessible in new ways, prompt people to reconsider what is being said.

Well, and just as a last comment, something about your work reminds me of YouTube, not unsurprisingly, I suppose…

What can I say? Those guys copied me…! But on a more serious note, I don’t find it surprising at all when different people arrive at similar forms at the same moment. If everybody eats the same food, we’re bound to end up occasionally shitting the same shit!

This interview orginally published on apengine.org (now defunct) in September 2009.