Vassily Bourikas is the programmer of the Experimental Forum at the Thessalonikki Film Festival. His passion for the format combined with an exceptional ability to root-out lost and forgotten film artifacts make for viewing experiences quite unlike any other. His Amantes Sunt Amentes programme for instance, seen at last November’s 50th edition of TIFF, brought together unknown 8-gage films by the Serb Ljubomir Simunic; an equally obscure feature-length film made by Hollywood character actor, Timothy Carey; Super-8 epics from Jeff Keen, an overlooked progenitor of the early British underground; and sui generis feature film experiments by the mad Italian theatre director, Carmelo Bene. Seen together, these films have the effect of demolishing notions one might have that experimental film is a completed project. Conversaton with Bourikas reveals a deeper connection between the films he programs and his perception that exisiting orders, whatever they happen to be, can always do with some disruption and reordering from below. I spoke with Vassily in Thessalonikki, after we had shots of raki he had been given as a gift, and before he had to rush off to present another one of his programmes at the Festival.

I guess we could start with an observation. Your programming is quite distinctive I’ve followed what you’ve done here pretty closely and I thought that there was a common denominator—in pretty much every film there is nudity or sexual content and gunshots…

Is there!? I never noticed that.

Yeah! But that’s specific to what was happening at that time; and to your interest in experimental film from the 60’s and 70’s.

You mean the Serbian Kino Clubs programmes or in all the programmes?

All of the programmes, I mean they’re all experimental to a certain degree, so I just wondered if you could elaborate more on that interest …

I thought that too, when I saw the films in the cinema with the audience, I thought, “Hey there’s a lot of tits in this film!” But not in most films, it’s just what stays with you, maybe. Because if you think about it there’s some nudity in maybe one one film per programme of the Serbian Kino Clubs. There is nothing like that, not a single gunshot or a naked person in the Ex-Yu Experimental programme.

But there were gunshots in the Ex-Yugoslav programme! On the soundtrack in Vlado Kristi’s Poor People (Arme Leute) (1963). This really spoke to me about the time that these films were made, there was a lot of tumult.

This was a time of turmoil in the streets–and in the jungles–but it was also the time when avant-garde cinema all over the world was laying its theoretical foundations. Avant Garde scholarship is still very much devoted to work from that era. Material and structural films, were developed then. Most of the avant-garde filmmakers we revere today made their mark around that time. But many of the films in these programs are not part of that canon and have not made their mark yet. So I didn’t really focus on whether there would be gunshots or not in them, the fact they were made at that time was good enough a reason to want to put them in this “picture”.

Military sounds, drumming, marching, and nudity. It’s expressive of the time, there’s an expression of freedom and anti-authoritarian attitudes, and this goes with the form of the films…

I think it just happened those days, from the early 60’s till the mid 70’s, that people expressed themselves differently and used the form as they felt. Like Tweet’s Ladies of Pasadena (1972), which is a rather unique example, but also many other American films they did not obey rules, there were more stream of consciousness works back then. Films like Doctor Chicago by George Manupelli (1968) or Ron Rice’s Queen of Sheeba meets the Atom Man (1963), or what Jack Smith was doing. That’s when people were revolting against conformity in any way they could. But what is interesting is that you notice this same attitude at the same time even when looking at these most precursory expressions of film experimentation from Yugoslavia. It was similar in many other Eastern Bloc countries.

There was so much open-mindedness and originality in the experimental film in those parts of the world, and we don’t know about it. The issue is still with us today: Where do we look for this type of work, which is very important in certain ways for cinema and for media altogether?

So how did it come about that you did this programme of cinema from former Yugoslavia?

I was travelling a lot to Hungary by train, preparing programmes on Hungarian experimental cinema, which I find is equally neglected. There was a lot for me to see there, they have an organized archive. As I was passing through Serbia, I came across snippets of forgotten films at the AFC (Akademski Filmski Centar). I first came across a couple of films and some catalogues in Serbian. With the second visit I found a few more; and then I felt the need to go there again. Soon I realized, when looking at Yugoslavian cinema, not the mainstream, but the narrative fiction film from that time, that its techniques and themes where very progressive. In the early works by Makavejev, for example, you find extensive use of found footage, appropriated in a feature length fiction film made for the general public.

And that was done without much fanfare. So I thought, there must be interesting works from there. I mean, thinking about Amos Vogel’s book Film as a Subversive Art (1974). The cover of the book is a scene from Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971). It’s not a coincidence. Makavejev at that time epitomised the global subversive film, he was very open-minded, was not really concerned only about Yugoslavia, but was not ashamed to be from there. He was showing the world what was happening in his country, but at the same time looking at everywhere else.

As you said, it’s interesting to show that certain cultural currents are global and may move through different societies

Yeah, It’s just that now we don’t remember and acknowledge this. I learnt a lot about that last year because of the programmes we did with Ivan Ladislav Galeta. He taught me a lot about a festival called GEFF (Genre Film Festival) in Zagreb. A couple of years ago there was a GREAT presentation at the Rotterdam Film Festival about the history of another Festival, the equally important Knokke-le-Zoute. This festival was held in a small town in Belgium and in the early sixties was also hailed as a key event for avant-garde film in Europe. I guess it still is. It was a really international event with important artists from all over the world. But there was very little work from the East of Europe at Knokke Le Zout, as if nothing of the sort was produced on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

At the same time there was this GEFF festival in Croatia, it started in 1959—so it was Yugoslavia then—showing works from the West as much as from the East. People were very open-minded about film, there were a lot of philosophers and even clerical philosophers—theologists and writers—discussing cinema, but also theater poetry, all the arts. Galeta told me that back then certain films like Le Chant D’amour (1950) by Jean Genet were banned in France, but you could watch them in a state funded festival in Yugoslavia.

People forget how cosmopolitan Yugoslavia was up to about 1972. I don’t know much about politics, but I can imagine that the early days of Socialism in a country like Yugoslavia–which was not even Stalinist–would be interesting. We never really think about it, but this is a country that has been penalised more than any other–not Serbia the whole of Yugoslavia–in the region after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Whereas before that, it was the land with the most liberal model of Socialism in the east of Europe. So I was really curious to see what happened there in an artistic way. And I’m not talking about artists like Marina Abramović, who had a career abroad, but the people who stayed there, those we never really hear about.

What you find out if you look at the credits of those films is that these filmmakers who experimented in the Kino Clubs worked very much together, despite their different ethnic backgrounds, which later caused civil wars. They loved each other, exactly those were the words of one of the people interviewed for our publication.

They loved each other because they were all artists, he told me. I do believe that; they were people living in urban environments, caring about the exchange of ideas. Being an artist back then and over there seemed to me to be different concept from what we are used to today. When it came to what they saw as avant-garde cinema, there were different systems and ways of thinking in the different parts of Yugoslavia. But there were very good ideas in every area, and they were blending together very well. It was a period of vitality in that country and I think it’s one that we should explore, not just in experimental film.

I thought all the films you showed in the Experimental Forum had in common a kind of a sensibility, as I mentioned before, a lack of concern for conventions, or the desire to explode the conventions, and an anti-authoritarian very liberated attitude. I’m curious about what your interest is in this type of film?

Everything! I like everything, as long as it’s free. ‘Experimental film’–that category–the way that it is pigeonholed, is actually quite conservative, in my opinion. We must look for what is really free, and we must show it. We should not manufacture it. Especially with the kind of film that claims to be an experiment.

The Ex-Yu films we showed were made in film clubs by amateurs, there was no ambition to become rich or famous through that work. In Yugoslavia there was freedom at a certain stage, or at least people believed there was and that they could make what they wanted to. Until the authorities took notice and pulled the plug on them. This entire historical and political context became for me a very interesting area of focus for my presentations at TIFF.

And the idea of being free and of doing exactly what you love made me think more about the concept of amateurism. Which is not about being an amateur in the sense of not caring too much about detail; it’s more about really loving what you do and not having any aspirations for getting financial reward or glory from it. This leads to the next big section of the Experimental Forum, which was called Amantes Sunt Amentes; that is Latin for “lovers are lunatics”. The word Amantes is etymologically quite close to the word ‘amateur’. I wanted to say that many of these filmmakers were people who desperately needed to get their work produced. And I think we have so much to learn from them. One can take the path of professional industry run cinema. The professional cinema will always have possibility to reach more people, because its structures exist almost since the beginning of “cinema TIME”. But for me it’s ridiculous to think that we are facilitating a professional structure of experimental or avant-garde cinema production, because such a thing shouldn’t exist, you know, and it does.

Can you define what that is, the professional structure of avant-garde?

Okay well, I mean I don’t know if I am going to get people upset for saying this, but I think there are a lot of filmmakers who are creating the work based on what already has been done, what already has been approved, historicized . That is often apolitical or minimal or basically, shall I say, superficial, based on very vague philosophical notions and ideas that could be talked about forever but they don’t have any relevance to people. The general public is not expected to understand. I am concerned about a certain regurgitation of concepts and subjects, a repetition of formal treatments. And one notices that much of this work is the result of a regular cooperation with academic structures, arts councils, and perhaps festivals .

In every profession, there are people who always manage to get as much as they can from a given condition, like a situation that supports the arts, and they can do it well. And it’s good that this support exists, because the arts need to be funded. But art councils and film festivals shouldn’t just create a circle of the “funded” and “supported” for a standardised kind of experimental film work, produced by the same people and their artistic offspring. In the feature-length film sector, it is not uncommon for important festivals to fund a production, then to select it, maybe even give it a prize; or national film funding authorities that fund certain films and then make sure that these films have to be shown.

It shouldn’t be like that in the realm of experimental film. It should be more free. It’s good to fund some filmmakers, but it’s also really important to go and find those that never got funding and never got help and still found ways to get their films made. And to give them a tap on the shoulder, even if they don’t need it. When I see that the type of work that doesn’t get much attention and is not going to be shown, whereas other films are repeatedly shown from festival to festival, the same people, you know, the same organisers and the same structures, then, yeah, maybe I will make that decision and say, “I’m not going to show any of that because it’s going to be shown anyway. I will go find something else; there has got to be something else. “

It’s a good project to expand or dismantle the canon, and to show that it’s still living. I think this is what your programming does is show that this type of film is not just solidified into this thing in the past, but is still really alive. Jeff Keen’s films, for instance, are incredibly fresh. Carmelo Bene–this is like almost nothing I’ve ever seen before. I felt so energised by it, and the Yugoslav films as well.

I think it’s not just about considering different countries that do not get shown as much, like Serbia, but it’s also about different modes of operation, about how people worked. Like maybe people wouldn’t put Carmelo Bene in an Experimental film section, but why not? Why does Experimental film need to be short or really long? Or why should avant garde film have no actors and acting in it? What rule says that this is not an experiment, if it is as free and as radical and philosophical and weird? Because it’s not about originality, these people are not looking for a gimmick that would set them apart.

They are just what they are, and I find that free. I feel that art is, by nature, something that should oppose the structures that suppress us. It’s about expressing yourself against whatever everybody else says. These films, like you said, they show that this thing is still alive, we haven’t closed that circle. Maybe those people were forgotten on purpose or by accident, I don’t know, but if we like their work and if we think that it is valid today then we should go back and find it. It might remind us that we can also do this for what’s going on today.

So that leads me to the question about your method of discovering these filmmakers who’ve been forgotten, like Timothy Carey or Ljubomir Šimunić?

I think everybody has got some sort of spider sense, or something, and sometimes you just see a photograph and you think, “What’s this?” And then you ask a question, and then you get a first answer, and you start realising that something is interesting there, and sometimes it works out, sometimes it doesn’t. It’s just if you carry on asking a lot of questions you might get some interesting answers, and if you lift up a lot of rocks you might find something somewhere underneath, so you’ve just got to do it often.

And you are creating a platform for this…

A small platform. I think that this would be nice if it remains a small platform because there are a lot of other important things out there to do in many aspects of life. But if we had a lot of small platforms it would be a lot better because then we could choose. Rather than everyone going to one big platform, if all these little small platforms were left alone and free to decide who they want to play with, then it would be interesting to see what happens when they come together and big platforms or bigger meetings could occur, but they would done freely.

The Thessaloniki festival gets impressive audiences, big audiences, it doesn’t matter what the time of the day is. And they largely stay at the screenings, they’re interested. I thought that maybe there was an ability to access this material because it’s retrospective and also the programming is identified with a region…

Not all of the films are about the region, I mean we showed Harun Farocki’s “In Comparison” (2009), and loads of people came to see this great film. But what impressed me is that people carried on coming, and on the weekdays too, and that’s nice. And it’s interesting that these are people from all walks of life; we’re not related to each other, like often occurs in such film screenings .

It’s not a ghetto.

It’s not an artistic ghetto definitely. You see people from all walks of life, all ages, all type of financial strata. I knew that from last year and I was impressed and that’s what gave me the energy to carry on working harder this year to make a bigger programme. In my introduction for the catalogue I was asked to answer the question that was the motto for this year’s festival, which is: ‘Why Cinema Now?’

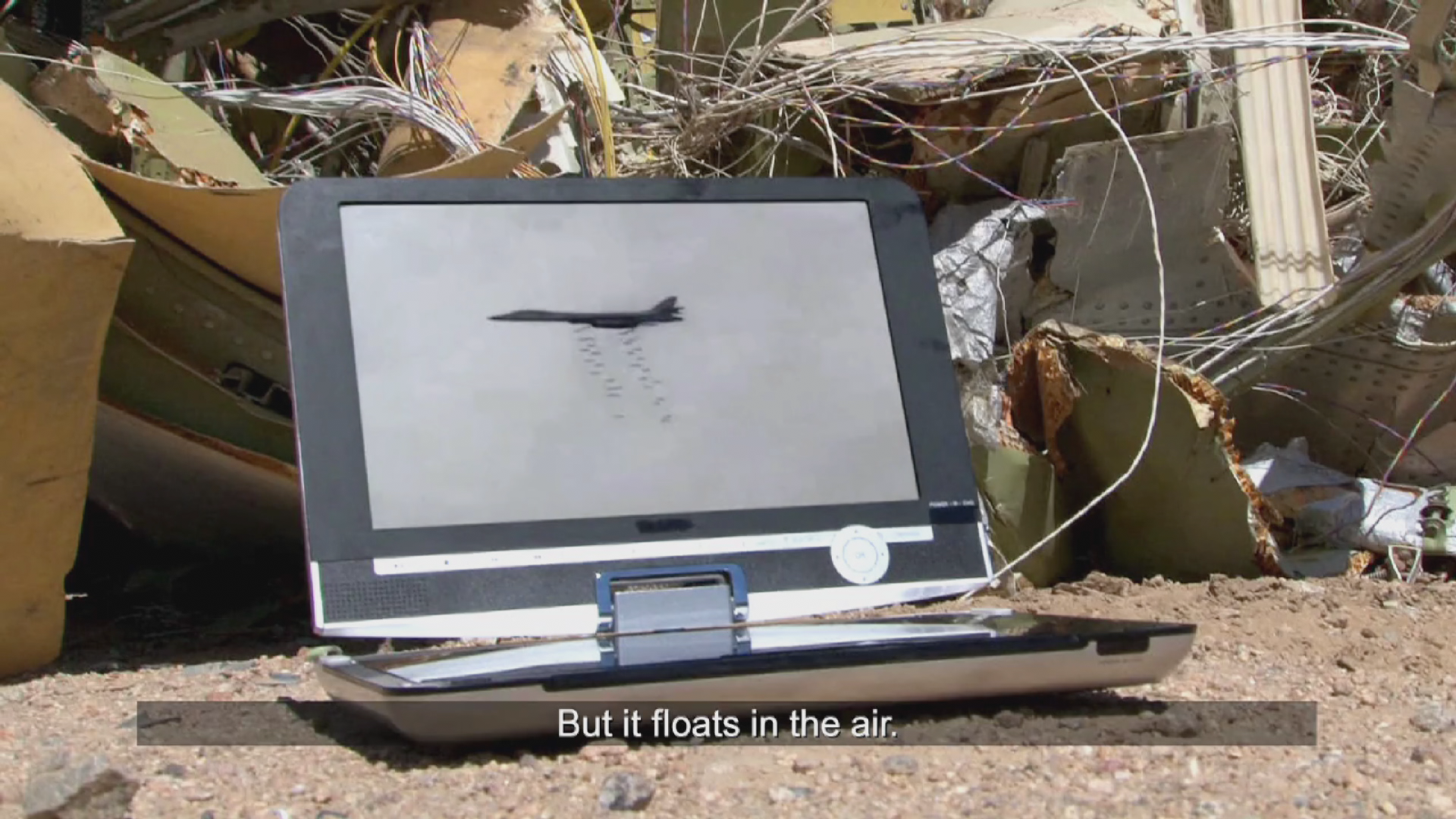

It was a peculiar question but it made me consider my involvement with experimental cinema. To me its important not to take cinema away from the traditional audience of the movies, which is pretty much everybody in a dark room not aware of what the other person is wearing, what they look like, how pretty they are. But you do know what they feel, maybe, how they gasp or how they cry or how they laugh, which is what you do in a dark room. I thought it’s an important question and that we could answer it with programmes that say: “Experimental cinema can be interesting now”. I think it’s a question I would like to carry on answering for a while: Why do we do it? Who do we do it for, basically? Is it just for a bunch of people somewhere else? What’s the point to be avant-garde when you’re the avant-garde of nothing. The avant-garde is a scout , in military terms, for the rest of the bunch; it seems now we’ve got an avant-garde that’s leading just itself. And doesn’t give a shit about where anybody else is going.

This interview originally published by apengine.org (now defunct) in spring 2010.